Where those who've lost are the winners!

01/09/2018

Updated on 09/20/2022

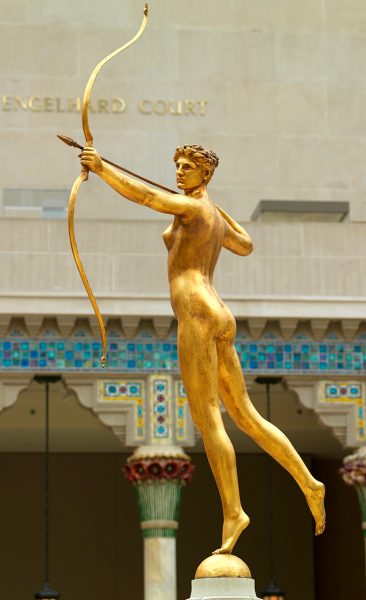

I’ve probably been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art about 60 or 70 times over the years, and I’m pretty sure I’ve seen every gallery there, but I haven’t always given pieces the proper attention they deserve. Then again, how could I? There are millions of pieces from all over the world and from all different time periods, nine times out of ten have no idea of the significance of what I’m looking that other than it may look pretty darn interesting (which isn’t a bad thing, really). Many times have I walked through the courtyard of the American wing and seen the gilded statue of Diana by the American sculptor August Saint-Gaudens. I even stopped to once or twice to really take in its lines and beauty, but I knew little of its historical significance other than what was written on the little explanatory card the curators placed near the statue. It was not until after I put together the entry on “The Second Madison Square Garden” did I realize the work’s historic, artistic, and local significance.

On a recent trip to the Met to see the “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman & Designer” exhibition (a lot of interesting sketches and works by the Renaissance master, but the crowds kind of killed it for me), I stopped by to view with fresh eyes Saint-Gaudens’ Diana. It is indeed a fine and striking piece of art, but one that I probably wouldn’t have ever put on top of a tower. It’s far too pretty to look at up close.

With that as my inspiration, I thought I’d empty out the notebook from the Madison Square Garden article, specifically the bits about Diana that I didn’t get to include, and present them here.

One of the more fascinating and striking bits of New York art and architectural history can be found at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met). There resides one of several half-sized casts of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ magnificent Diana statue, which was based full-sized version that once occupied the main tower of Stanford White’s magnificent Madison Square Garden. This version of the sculpture, although not full-sized, is a particularly fine piece of to make a study of not only because you can you get close to it, but you can walk around and get a 360° view of Saint-Gaudens’ gilded work. The original Diana, which has been lost to time, was replaced atop the Garden in 1892 by a second version of the statue. It was from this second version that Saint-Gaudens made his half-sized copies including the one that resides in the Met. As for why there were so many versions of the same sculpture and why they ended up where they did is a story of an two artists, a once-great building, and a big miscalculation.

This was the first version of Diana at the W. H. Mullins Manufacturing Company in Salem, Ohio, where the statue was cast in 1891. If you look closely, her foot is connected to her base rather inelegantly at the heel. This pissed off Saint-Gaudens and White to such a degree that they used their own funds to replace it with a smaller second version. The newer Diana was smaller and had a slightly different orientation. (Public Domain)

Take a look at the SilverMedals.net article on the Second Madison Square Garden for a more in-depth account of the building of the second Garden, the famous architect Stanford White who designed it, and how he got his famous sculptor friend August Saint-Gaudens to create the sculpture of Diana to adorn his new Garden. In short, White wanted there to be a work of art on top of the tallest tower of his Madision Square Garden to act as not only an artistic symbol for the city but also as a weather vane. Saint-Gaudens for his part created Diana, an image of the nude Greek goddess drawing her bow, the only nude work Saint-Gaudens ever produced.

Saint-Gaudens wanted his statue to be striking since it was to be on top of a tower, but also graceful and classic. To create Diana, Saint-Gaudens used two models for the statue — Davida Clark for the head and Julie “Dudie” Baird for the body. Clark (born in Sweden and originally named Albertina Hulgren) had posed for Saint-Gaudens in the past and had been romantically involved with the artist since the early 1880s. Saint-Gaudens carried on his extramarital affair with Clark until just before his death in 1907. The relationship provided Saint-Gaudens not only with a loving companion, but also a model and inspiration for other works, and a son. As for Baird, she was a famous model and had posed for many famous artists at the time. To create the correct dimensions for the sculpture’s body, Saint-Gaudens took several casts of Baird’s body to use as reference.

Saint-Gaudens made a model version of the statue before sending it out to Ohio where it was caste in copper, bronze, and steel. It was a truly magnificent work but not a very sensible one because there ended up being four major problems with Diana that needed to be rectified.

First, it was freakin’ huge. When cast, Diana measured about 18ft tall and weighed about 1800lbs. As a weather vane it would have taken one hell of a wind to move her even with her big circular metal drapery or “foulard” that was attached to help capture the wind. So the weather vane idea was out.

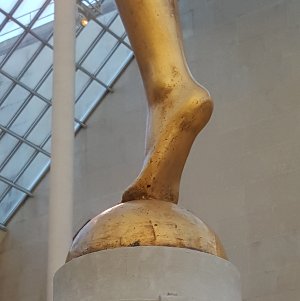

Here is a detail picture of the Saint-Gaudens’ half-sized copy of Diana at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York showing her attached to the base on the ball of her foot. The original statue had to be attached at the heel to accommodate the enormous size of the piece. A minor issue yes, but to the Saint-Gaudens, it was an eyesore. (Photo by SilverMedals.net)

Second, being so huge, she looked out of proportion with the rest of the building on top of the tower. It’s a mystery today as to what White and Saint-Gaudens were thinking when they first came up with the proportions, but they were shocked when Diana was lifted into place. It simply looked weird to have this lovely majestic tower capped with a gigantic, comically inelegant statue.

Third, because of the statue’s ridiculous size, when the it was cast at the forge, the guys casting it found that the statue wouldn’t be stable when standing. Specifically Diana‘s front foot, she was supposed to be standing on top of a sphere leaning forward on the ball of her front foot, which would have been elegant and graceful, but because of the size of the piece which necessitated running a support rod up through the heel of her front foot, instead of standing on the ball of her foot, she had to be connected to the base through her front foot’s heel and stood a bit straighter up that she was designed. People standing below and looking up at the statue probably wouldn’t have noticed or even given a crap even if they were made aware, but for Saint-Gaudens, it was a burr in his artistic psyche knowing she wasn’t standing as she should.

Finally, the fourth problem with Diana was the fact that she was naked and got under the skin of the prissy, puritanical, squares in the late 1800s. To them her nakedness was an affront to their sensibilities and in their eyes, pornographic, and they made their opinions known quite loudly. They may have had a practical point there. Apparently men back in the day were so hard up to see naked women that telescopes were set up in Madison Square Park where some Victorian-era perverts could gaze upon Diana‘s lithe figure as she stood al fresco over New York. This issue at least had an easy solution. To pacify the prudes, White had a cloth draped over the statue to cover up the her private bits. This shut up the critics, but the solution didn’t last. Over time the winds tore the fabric off the statue, returning Diana to her naked state. At some point, however, it seems the outcries died down.

Here is the “second” Diana as she stands today at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In 2014, the museum completed a restoration of the statue to restore it to its former gilded glory.

The other three problems couldn’t be solved with a cloth, so White and Saint-Gaudens had the statue taken down at their own expense and replaced with a smaller version. This time around the two artists were more cautious. Before the final crafting of the “second” Diana, they hoisted onto the tower a sort of dummy version of a smaller Diana made of clay and metal to see if the new statue would more or less “fit” on top of the tower. It only remained up there for about 10 minutes because: 1) White and Saint-Gaudens didn’t want to have an unfinished study version of the statue up there for long, and; 2) it was January 1893 and nobody wanted to be high up on a tower in the cold, windy, New York winter longer than necessary. In the end, the new dimensions seemed good enough for the two artists, and in November 1893, the newer, smaller, 13-foot, 700lb version was installed on top of the tower. Of course, the nakedness issue didn’t fully go away, at least some including the New York World newspaper found some levity in her depiction when it printed the following thought:

“Perhaps the new Diana of the Madison Square Garden tower is intended as a protest against the prevailing extravagance in dress.”

One thing that seems to appear and disappear in various photos throughout the second Diana‘s existence is the copper metal foulard that was there to help catch the wind. On several occasions, this bit of metal broke off and needed to be re-attached with wires to stay put. After a few more tries to keep it on, the Madison Square Garden owners did away with it and for the most part dropped the whole weather vane idea.

Diana at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. (Public Domain)

Stanford White very much liked Saint-Gaudens’ improved Diana and decided he wanted a copy of his own. So in 1893, White commissioned Saint-Gaudens create a concrete half-sized replica of Diana, which he placed in the garden of his Box Hill estate on Long Island, New York.

The only nude sculpture that Saint-Gardens ever produced, it also became possibly his most widely known work, and one that the artist himself chose to capitalize on. Several more half-sized copies were cast, two of which reside in the Saint-Gardens National historical site, one at a museum in Texas, another at the Princeton University Art Gallery, and another, perhaps the finest of them all, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

It’s of no little significance that such a lovely cast of Saint-Gaudens’ creation today resides in New York. The Diana statue was once a well-regarded piece of the growing city skyline and produced by one of the city’s finest artists.

The original huge Diana after it was taken down was shipped to Chicago where it stood over the Agricultural Building during a the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. It was then taken down, put into storage and then destroyed by a fire (actually, half of the statue was destroyed in the fire, the rest was likely sold for scrap). The second Diana after it was taken down from Madison Square Garden before its demolition was originally supposed to go to New York University to be placed upon its main campus building which in those days was in the Bronx (today it’s at Washington Square in Manhattan).

Here’s a tiny version of Saint-Gaudens’ Diana, which usually resides in Gallery 769 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. (Public Domain)

When White’s Madison Square Garden was due to be demolished in 1922, the New York Life Insurance Company, who owned the site, didn’t really want Diana, and were considering scrapping the piece. A group of NYU supporters stepped in with a plan to raise the funds to purchase the statue. New York Life agreed, but the deal never happened. NYU was unable to raise the money and the statue ended up in storage. After about a decade in storage, New York Life ended up donating the second Diana to the Philadelphia Museum of Art* in 1932, where she resides to this day in an appropriately prominent spot.

So the two most widely viewed Dianas both New York landmarks in their time ended up away from the city they once adorned. This wasn’t and isn’t an Earth-shattering issue — New York has many symbols and landmarks to call its own — but it adds to the poignancy of a long-forgotten icon of Gilded Age New York. The city like most of America during the time of Saint-Gaudens and White changed rapidly and unsympathetically with many beautiful old buildings destroyed to make way for newer ones. The Met Diana at least in a small way preserves some of that history.

*Coincidentally, the crazy guy who shot and killed Stanford White at Madison Square Garden’s rooftop theater — underneath the Diana statue on the tower — was from Philadelphia.