Where those who've lost are the winners!

07/01/2019

Updated on 11/01/2022

It didn’t have as compelling a birth as the first Special Air Service regiment. It didn’t have its great founder driving point in a souped-up jeep during attacks on German air bases. It didn’t have the romance of the desert as its initial stomping grounds. About the only thing it seemed to have going for it was the reputation of its elder-brother regiment whose members were very skeptical of the younger’s ability to do the job. As a whole, even historians overlook it as an entity on its own, but instead group it in with other SAS units as part of a broader history with little analysis of its long-term influence and its special place in UK special operations history. But the second regiment of the lethal and highly trained Special Air Service of World War II was more than just another elite unit that did daring things, it was one of the most important units of WWII and may have had the biggest influence on all post-war special operations forces both in the UK and in other western countries. Known as 2SAS, it was the second Special Air Service regiment ever commissioned by the UK.

The UK’s 22 Special Air Service (SAS) regiment today is one of the world’s finest special operations forces and a wholly unique military entity. There are other special operations forces around the world, but none that have the same culture, history, breadth of training, or esprit de corps as 22 SAS. Having been in operation for almost 80 years, it is the standard by which all the world’s special operations forces are measured.

SAS operators are trained in all the things one would associate with elite special operations soldiers. They are trained in unconventional warfare, weapons, vehicles, explosives, intelligence, counter-intelligence, surveillance, counter surveillance, close combat, hostage rescue, advanced infantry tactics, advanced parachuting, jungle warfare, alpine warfare, urban warfare, desert warfare, warfare warfare, protection, close protection, languages, how to train other forces, management, navigation, survival, evasion, waterborne operations, and any training specific to whatever operation in whatever part of the world as is necessary. Think of them as really smart professional athletes who will do whatever they need to do at any given moment, and who will never give you the full story of how they operate.

SAS operators from WWII to today rely on guile, surprise, stealth, and cunning more than any bomb, bullet, or knife to achieve their mission goals (although they can just as easily bring the big guns when the mission calls for them). Even their name, Special Air Service, was a somewhat cheeky effort at misinformation in a fashion that was uniquely British. For only the British could have referred to the most lethal combat group of World War II as a “special air service”, a name more suitable for an airfreight delivery company than a fighting force.

One of the main things that set SAS operators apart from other soldiers is not their physical presence or any particular aura of bad-assery, but their patterns of thought, confidence without overconfidence, attention to detail and planning, and their situational creativity. This is a fact of most top-tier special operations soldiers, but the SAS was specifically built on these qualities from is earliest days in the North African desert. Those WWII SAS soldiers were extraordinarily audacious not just for their time, but even for now. One SAS operator once walked 150 miles through Saharan desert, with barely enough water to fill a Dixie cup, to get back to his own camp rather than surrender (a feat later repeated during the Gulf War). Another, after conducting sabotage missions in Northern Italy, walked the length of the Italian peninsula through the mountains all the while evading German patrols over a period of several months to get back to friendly lines. One group while on a mission in Libya lied their way out of trouble in Italian-occupied Benghazi by pretending to be officers on the “General Staff”, going so far as to rebuke several Italian sentries about their lax security. Two more did a similar thing in Italy when they walked through a German-occupied town right past a German sentry who spotted them but didn’t fire or raise an alarm — possibly out of shock but likely because he knew he would have been the first killed if things went kinetic. There are several accounts of SAS soldiers who while working with maquis or resistance groups in occupied France would frequently go into town to eat in restaurants as if the area wasn’t teaming with German Gestapo agents and fascist sympathizers looking specifically for British agents. In the middle of an operation in southern Italy, two SAS soldiers left their posts to go looking for a pub in a nearby town while German panzers were moving through the area. One group of SAS soldiers, without any official authorization, kidnapped a suspected German war criminal in Soviet-occupied Germany and spirited him into the French sector to bring the him to justice. Even two of the founders of the SAS — David Stirling and Blair Mayne — after a friendly argument over who had destroyed more enemy aircraft during raid they had just completed, got into their truck, drove back toward the airfields where they had JUST sabotaged a bunch of aircraft and where enemy soldiers were on full alert, to have a look at the aftermath of their mission all so they could see who caused more destruction. (Apparently Stirling won out that time, but it must be stated that it was he who later told the story.)

One doesn’t want to use a word like “crazy” to describe these very brave and very capable soldiers, but as one former 22 SAS veteran of almost 20 years once remarked, “We were all barking mad!”

The SAS insignia, it was designed by Bob Tait who was one of the “original” members of L-Detachment. The image depicts the mythical sword Excalibur (not a dagger as many people even SAS guys themselves refer to it) as a symbol of British strength, with blue wings. The blue wings represent the unit’s roots as an airborne unit. The motto “Who Dares Wins” was David Stirling’s. He was the founder of the SAS.

There were were a total of six SAS regiments raised during the war. Formed in 1941, the first SAS regiment and the most famous was the prototype and the first to prove the concept and overall operational efficacy of the unit. The second regiment we will get to in a bit; the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth SAS units were made up of French (3SAS and 4SAS), Belgian (5SAS), and Dutch (6SAS) soldiers. All of those regiments were either dissolved or were repatriated to their own country’s armies and subsequently absorbed into new units after the war ended. But the British SAS for a brief period in the post-war years ceased to exist until world events compelled the UK to reinstate them.

Today there are technically three SAS regiments in the British army. They are 21, 22, and 23 SAS, although two — 21 and 23 — are reserves and are listed as SAS(R). In almost every possible way, it is 22 SAS — commonly referred to as “the regiment” by members serving today — that carries the mantle of the original units first formed in WWII.

As with most “firsts”, it is the first SAS regiment — the one “born of the desert”1 and the one that became a very long thorn in the side of the German Afrika Corps — that is the most widely known and celebrated. It was a colorful unit with a colorful cast of characters — the stuff of Hollywood fiction — but when you look at the subsequent history of the SAS, what it was and what it is today, it was the second regiment of the SAS, 2SAS, that had the most significant impact on its long-term success. Without a doubt, it was the bridge between the prototype 1SAS and the contemporary 22 SAS, and for all other of the world’s special operations forces who owe some part of their existence to the original SAS.

This is not an article about the history of 22 SAS, or one entirely about the history of the SAS in World War II (although there is a lot covered here). If you wish for a fuller history of the early SAS, please refer to the Recommended Reading section at the end of this article. Several of the books listed there were used as reference material for this piece. This is the story of 2SAS — its history and its impact . As with most things that come second, to understand 2SAS, we first have to tell the story of how and why the SAS was formed along with the personalities that formed it. It all began in the arid, desolate, and inhospitable North African desert where the British army was fighting off the combined German and Italian armies in the early days of WWII.

No article dealing with the early history of the SAS would be complete without this photo, possibly the most famous one ever taken of SAS soldiers. Notice the twin Vickers guns mounted on the jeeps, they were used to shoot up German and Italian planes on the ground during raids and to rip through troop formations. Apparent here also is the “unsoldierly” look they adopted with beards and uniforms that were in no way regulation. This caused many officers in other units to regard the SAS as unkept, unbalanced, and undisciplined. They were anything but undisciplined.

The United Kingdom in the beginning of 1941 was alone. With no significant allies remaining in Europe, they stood as the only world power operating against the German and Italian armies not only in Europe but in North Africa, the entire the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean, and in the Middle East (against mainly German-allied Vichy French forces). The “arsenal of democracy” U.S. was still about 11 months away from being attacked by Japan and pulled into WWII, and Soviet Union was not yet an enemy of the Axis.2

Events in the North African desert had so far gone well for the British who had previously repulsed an Italian thrust toward Egypt, then a UK possession, but their position was again growing precarious. Italian forces backed by Germany were again threatening Egypt and its all-important Suez Canal, the loss of which would have forced British boats sailing to and from India and Australia, also British possessions, to have to go all the way around the tip of Africa. In addition, the loss of Egypt would have given the Italians and Germans a direct route into the Middle East, its oil, and a nice backdoor route into Asia to potentially link up with their Pacific ally, Japan.

As the Italian army pushed into Egypt, it was essential for the British to obtain reliable information on the strength of the Italian army and how quickly they were moving supplies along their main supply routes. The group that was formed to address this need was the Long-Range Desert Group — a deep-penetration reconnaissance and raiding unit. Formed in 1940, the unit was made up entirely of volunteers who came from various ranks in the British army, along with a sizable contingent of New Zealanders who were farmers in civilian life. But the most important volunteers were a group of English cartographers and cartographic enthusiasts who before the war had spent many months exploring and navigating the Sahara Desert. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, these desert explorers had made several expeditions deep into the Sahara to places that had never previously been mapped. They were uncommonly adept at desert navigation, and they had a knowledge of the desert that few Europeans or even most locals had. Equally important, they knew how to drive and modify vehicles for service in the desert, which was a very specific skillset that few had.

Soldiers of the Long-Range Desert Group in 1941. Before the war, many of its members were cartographers who made several trips into the Sahara to map its previously unmapped interior. They developed techniques and equipment to make desert travel in jeeps possible. (Imperial War Museum)

During those tense early months in North Africa, the LRDG conducted numerous surveys and reconnaissance missions, which took them deep into the desert, around enemy patrols, and north toward the main Italian supply roads that ran along the coast. What was remarkable about the LRDG was their ability to drive into the desert to avoid enemy spotter planes (there were few because the Italians and the Germans did not think that anybody in their right minds would ever try to navigate so far into the unforgiving Sahara) and then navigate toward precise points on the North African coastal supply routes. These were the days before GPS, satellite imagery, or any type of advanced electronic terrestrial navigation. Instead they used modified sun compasses3, which required a high level of expertise to use over the vast distances in the featureless desert. Even the slightest error in calculation could result in being off course by hundreds of miles.

The LRDG didn’t just watch roads, they also made several small and limited attacks on elements of the Italian army. But their real contribution was in providing information on enemy movements, and ferrying personnel into areas behind enemy lines. The information that the LRDG provided for British 8th Army between 1941 and 1943 contributed directly toward their successful stand in Egypt and eventual success against the Axis in North Africa. When all is taken into account, it was the LRDG that first showed how effective an independent party of mechanized soldiers could be in operating deep behind enemy lines with little oversight or specific direction. They would also play a key role in helping to shape the future SAS.

In 1940 back in the UK, around the same time that the LRDG was formed and while the Italians were making their first thrusts toward Egypt, a new highly trained raiding force was being put together whose mission was to conduct large-scale raids on targets such as towns, ports, or artillery installations. They were called the “commandos” and they were trained to conduct their operations in groups of 100 to 500 soldiers usually without any support of armor, artillery, or planes. These men were trained to hit their targets quickly and then get out before any massed counter-attack could be mustered.

Commandos were some of the finest soldiers in the British Army, and at the time, they were the most well-trained and most audacious. In their early days, they conducted several important raids along the French coast, Norway, in the Mediterranean. One of the most famous raids was the raid on St. Nazaire, France, on March 28, 1942, when a large contingent of British commandos rammed a ship laden with explosives into a dry dock that was vital to the continued German naval blockade of Britain. The raiders blew the dock up and caused a considerable amount of localized havoc. It was after the St. Nazaire raid that German Chancellor Adolf Hitler issued a directive to his army — known as the “commando order” that any captured British commando was to be considered a spy and executed immediately.4 This order, ignored at first, was the reason for many later atrocities that were committed against uniformed British and American soldiers, even ones who were clearly parachute infantry and not spies. By the end of the war, at least 250 British soldiers and downed airmen are believed to have been killed as a result of this order. Interestingly, the commando order was not common knowledge in the British army until about 1944.

Over in the Mediterranean, a somewhat stitched together commando unit was formed to conduct operations in the Middle East. The unit, which altogether numbered around 2,000 soldiers, was commanded by Colonel Robert Laycock and came to be known as “Layforce”. They saw action at Bardia, Crete, Tobruk, and in Syria, but overall their success was minimal as they took steady losses in each engagement. Commando units were lighter quick-strike soldiers, who were best used not as heavily armed infantry in the middle of large-scale pitched battles. Layforce however often found itself thrust into the frontlines, a role for which it was ill-suited. The unit slowly bled off as casualties mounted and replacements didn’t materialize. By the middle of 1941, Layforce was reduced to a point where it was no longer combat-ready or able. What was worse was that morale was suffering greatly as the remaining members found themselves languishing on the edge of the Mediterranean undermanned and with no real purpose.

The misuse of commandos went beyond being thrust into frontlines, but they were also misused in the types of raids they conducted. Lt. (Archibald) David Stirling was an officer in Layforce who saw this first-hand. An eccentric and adventurous soldier from an aristocratic Scottish family, he thought deeply about contemporary warfare focusing on the use of commandos in large-scale raids and the goals which they were trying to achieve. Such raids had their place, but there were other strategic opportunities that were being missed, ones that could better be addressed with smaller units. Often times commandos went into missions with forces numbering around 100 to 200 men either by boat, parachute, or land. Because there were so many of them, they would be easily spotted once the operation began. Additionally, the force would be diminished from the get-go since half of the commandos would end up having to be left with their exit vehicles to guard them from counter attack. In the end they would always lose the element of surprise, which to Stirling was the most essential part of any mission.

Stirling more than any other person in those early days of WWII understood the need for a new type of force as mobile as the LRDG and as lethal as the commandos that could operate deep behind enemy lines taking out targets of opportunity, straining supply lines, and compelling the enemy to adjust their security to account for them. Instead of hundreds of men hitting a target with guns a blazin’ and shitfire raining everywhere, Stirling thought that small teams of 12 men divided into three fire teams would be far more effective. Each man could carry 5 or so bombs, and sneak into places that commandos could not. Since there were no vehicles to protect they could attack in force, and because there were so few of them the element of surprise would not be lost. If all went well, each man could plant his bombs with timed fuses and be miles away before those fuses went off leaving the enemy confused and shooting at shadows. Commandos, the manner in which they were used and trained, couldn’t do that.

Stirling shared his thoughts with Lt. John Steel “Jock” Lewes, a colleague from Layforce who was a well-respected officer in his own right, and who agreed with Stirling’s views. It can very easily be said that Stirling and Lewes were the first ever members of the future SAS with Lewes being its first recruit. Their conversations turned to actions which led the two to go on an experimental parachute jump to educate themselves on the practice. Neither had ever jumped out of a plane before so like most things in Stirling’s military life, there was a “learn as you go” aspect to the whole endeavor. In what was a rare moment of bad luck for Stirling, the jump went badly and he ended up in hospital with a broken leg and a spinal injury. He spent several weeks there with little to do but think.

Surrounded by maps and notes all over his hospital bed, Stirling developed his idea into a full-on memorandum. He believed that there were many opportunities for his force to be a nuisance to the Axis in North Africa, where there were many soft targets to hit along their main supply line. Blowing up supply dumps, mining roads, shooting up aircraft on the ground, blowing up bridges, cutting telephone lines — these were the disruptions that could help the Brits win battles before they even began. Especially in the North African desert, where most supply ran east-west over a narrow inhabited area along the Mediterranean coast, disrupting this supply line could be relatively easy. The main points he covered in his memo can be broken down to three:

Keep in mind, this would have sounded like a batshit crazy idea to most officers in the British army at the time. A bunch of small teams running around behind enemy lines blowing up stuff? It was almost too fantastic for fiction and it ran counter to what many understood as military orthodoxy.

Leaving his hospital bed, still with a broken leg and walking with a cane, Stirling went to the British Middle East headquarters in Cairo to pitch his idea. At first he was refused entry, but broken leg and all, Stirling snuck through the gate and into the building past the guards. He made his way into the office of a very surprised General Neil Ritchie who was chief-of-staff to General Claude Auchinleck, Comander-in-Chief of British Middle-East Forces. Despite the impertinence of the tall, hobbling, lower-ranked man barging into into his office, Ritchie was shockingly receptive and read Stirling’s memorandum outlining his ideas. To Stirling’s absolute surprise, Ritchie agreed with the premise of the memo and promised to act on it. Several days later, Stirling was brought in to meet Auchinleck and to make his pitch.

Contrary to SAS lore, it wasn’t just Stirling’s persuasive and charming personality that won Ritchie over. Ritchie himself had been entertaining similar thoughts in his head for some time, looking for any advantage the British army could gain in the desert war. He too saw the inherent issues in the large-scale raid concept, identifying many of the same problems Stirling found. What Stirling did for Ritchie was to come up with a solid plan to address those problems, one that Ritchie could use to convince his boss.

Stirling was very eloquent and persuasive as he pitched his idea to Auchinleck. Additionally his being from an aristocratic background put Stirling in a similar societal status as the general, which greatly helped grease the wheels of the conversation. He laid out his plans for putting together his force and discussed everything from the types of soldier he would recruit to the training course to the overall operations profile of the unit. Stirling won over Auchinleck and in July 1941 he got his permission to form his new detachment. He also convinced Auchinleck to create the unit as fully independent force within the army, responsible for its own training, recruitment, and operational planning outside the normal chain of command. Stirling had a very low opinion of British officers whom he colorfully referred to as “fossilized shit” because of their outdated views on warfare and and often times damaging reticence. Even more, Stirling had little use for bureaucracy and the chain-of-command, which he saw as a hinderance. He emphasized that his unit had to come directly under Auchinleck’s command to avoid the fossilized shit. Again, Auchinleck agreed, and along with his blessing, he gave Stirling permission to recruit six officers and 60 other ranks. With almost no oversight, no budget, no formal plans or documents of what the new unit was to be, Stirling went off to build what many referred to as “Stirling’s Private Army”.

It’s impossible to see anything like this happening in the British army today, and in fact, regulations were later implemented that would prevent such a thing from happening again, the chief one being that new units had to form within an existing one before it could be given a “Royal Warrant”. But those were desperate times, and Stirling gave his superiors an option that would cost them no more than some men and some equipment but promised to be highly successful. For Ritchie, Auchinleck, and the rest of British 8th Army, it was a pretty good gamble.

The person who came up with the name of Stirling’s new unit was Dudley Clarke, a very capable and forward-thinking British Intelligence officer who was at the time working in Cairo. Clarke ran counter-intelligence operations and disinformation campaigns in an effort to confuse Italian and German spies, even going so far as to make up phantom units complete with decoys and fake memorandums. He came up with the name “Special Air Service Regiment” as a way to fool the Italians into thinking there was a large airborne force in the area. When Stirling came along, Clarke agreed to work with him as long as the new unit adopted the name Special Air Service Regiment even though it was nowhere near the size of a true regiment. To further pad the deception, Stirling’s new unit was given the full name of “L-Detachment, Special Air Services Regiment”. The operators within the group initially referred to their unit simply as L-Detachment, before adopting the more general Special Air Service term, or simply SAS, as the ruse was no longer necessary. It wouldn’t be until September 1942 that the unit was redesignated 1SAS as more units were added to the SAS ranks.

Two of Stirling’s first recruits into L-Detachment unit were John Steele “Jock” Lewes, and Blair “Paddy” Mayne, both of whom are legends in SAS history and, even in the opinion of David Stirling himself, the most influential personalities in establishing the culture of the SAS.

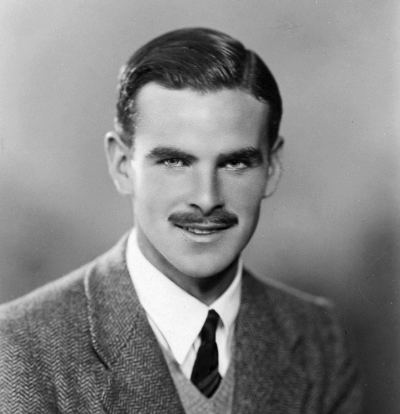

The dashing John Steele “Jock” Lewes, the first person Stirling recruited into L-Detachment.

Jock Lewes was a Lieutenant in the Welsh Guards before joining the commandos and being assigned to Layforce. Born in India, he spent his childhood in Australia before heading over to England to attend university at Oxford. A very dashing man of his time, he was highly intelligent and uncommonly accustomed to living rough having spent his youth rambling about. Most important, Lewes was able to think creatively and was always trying to come up with new ways to harass the Germans and Italians.

Stirling was very aggressive in his recruitment of Lewes, however, Lewes’ experience from LayForce made him very skeptical of Stirling’s idea and his claims as to how the unit would be run. Lewes also wasn’t sure what type of leadership to expect out of the tall Scot. But after much discussion, Lewes agreed to join up with the SAS and become its first training officer. This proved to be a very fortuitous posting.

Lewes devised a training program that was heavy on both physical training and tactical skills, and was designed to toughen their men mentally as physically. They were trained in among other things first aid, demolitions, vehicle handling, hand-to-hand combat, and desert navigation. They were also trained on using just about every type of Allied and Axis small arms available.

Lewes like Stirling believed in leading from the front, or at least demonstrating from the front. He believed deeply that he should never let anyone in the unit do or try anything unless he did it first. From running through a training course, to jumping out of planes ill-suited for parachuting, Lewes wanted to show the men under him what was possible so that they would have the confidence to do what needed to be done.

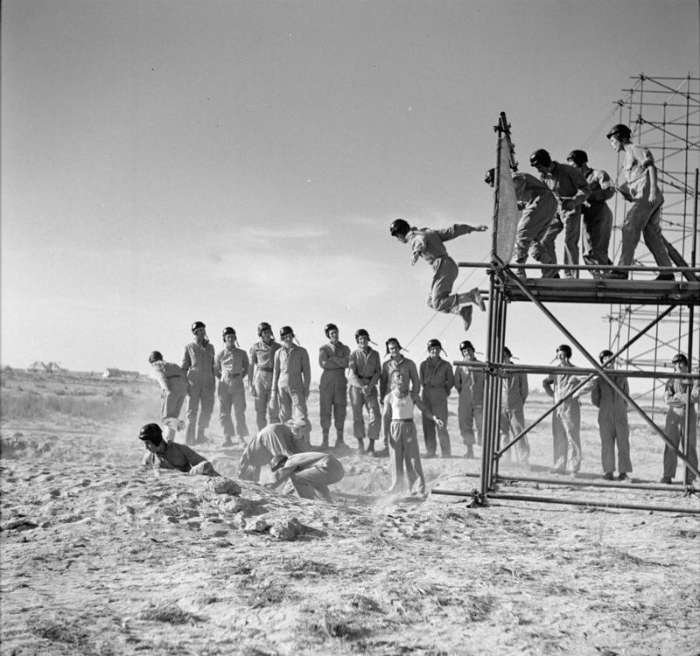

The men were put through grueling marches and runs in the desert while carrying full packs and weapons. There were also night maneuvers where men were taught to orient themselves in low light and to shoot at sound. There were no instructors or schools in Egypt for parachute training, so the SAS had to create their own, the early stages of which involved jumping out the backs of jeeps driving at 30 mph, and jumping off scaffolds all to teach the men how to hit the ground hard and roll. It was the overall feeling in the SAS that training had to be far more exacting than commando training, which itself was difficult. It was also important to use training to instill confidence in each soldier, which in the opinion of Stirling, was more important than anything else. He believed that with repetition and training, confidence would naturally follow.

As it is in today’s 22 SAS, there was constant evaluation of recruits. Failure wasn’t so much not being able to do something or not being quick to learn something, but rather a failure of drive. People outside the SAS then and today concentrate on the physical aspects of the job, but in reality, it’s always in the mental aspect where recruits failed. As is true with marathon runners and extreme sports athletes, SAS recruits had to overcome their fatigue and physical pain and keep going on with the task at hand. They may have made mistakes during their training, but those could be learned from and corrected. Mistakes where soldiers let themselves give up and stop due to fatigue were not as easily forgiven. As for Stirling’s SAS, if a recruit were to prove unsuitable he would be RTU’d (returned to unit).

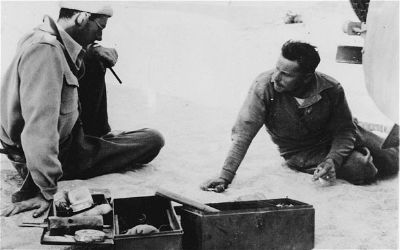

David Stirling (left) and Jock Lewes (right) in the North African desert discussing operations.

Among Lewes’ other innovations, he invented the “Lewes Bomb”, a special type of bomb made specifically to destroy aircraft on the ground, a version of which is still used by special operations forces today. Without getting too much into the chemistry or the finer points of demolitions, Lewes formulated a bomb that on detonation would not only provide a lot of explosive force, but would generate a high enough temperature to melt metal. There was also an incendiary element that would make a nice big fireball on detonation igniting anything within range of the blast. Prior to Lewes’ invention, demolition experts at the time hadn’t thought such a weapon was feasible since one portion of it would counteract the others. The Lewes Bomb ended up being a huge advance for the unit and made many of their missions possible.

Unfortunately for the SAS, Lewes was killed during a raid in December 1941 when the truck he was in got strafed by a low-flying German aircraft. He was hit in the leg and bled out within minutes.

News of his loss greatly depressed unit morale as well as Stirling personally, who had seen Lewes as both a kindred spirit and one who understood what they were building. Not only did they lose a fine soldier, leader, and SAS contributor, the unit lost a strong personality whose presence gave confidence to others. The SAS swagger was somewhat diminished, but the culture Lewes helped build still remained strong.

More than any other person, however, Blair “Paddy” Mayne was the ideal — quite possibly the finest SAS member there ever was. Born into a middle-class Protestant family in Northern Ireland, Mayne was a well-respected solicitor (lawyer) before the war and an accomplished amateur boxer and rugby player. He joined the commandos and like Stirling and Lewes, he was assigned to Layforce. Tall and athletic, Mayne was highly intelligent, affable, and spoke gently, but when it came to combat, he was a ferocious, violent, and vicious person whose courage was, without even a hint of exaggeration, super human.

For lack of proper instructors and facilities, John Steele “Jock” Lewes, one of the SAS greats, came up with the idea of training the soldiers of L-Detachment for parachute drops by having them jump out the backs of jeeps as they drove over the desert at speeds as high as 30mph. This resulted in a number of broken bones.

Mayne was also a difficult and violent drunk. He would often throw punches at anyone who crossed him during his drunken states, making him a bad person to be around in pubs. It was a startling change for many who knew Mayne as a quiet, very polite, almost reserved person. Other officers would avoid him whenever he was looking for someone to drink with. It was due to his being a violent drunk that Stirling came to meet Mayne.

In one incident before he was in SAS, Mayne drunkenly punched a superior officer and ended up in a Cairo jail. While Mayne languished, a friend of Stirling’s from Layforce recommended Mayne for inclusion in the new unit. Mayne had distinguished himself during a battle against Vichy French forces in Lebanon at the Litani River, and he had a reputation as being a capable and professional soldier. He also apparently hated superior officers — perfect for L-Detachment.

Interestingly enough, Mayne’s self-destructive drinking helped push him into L-Detachment. Unlike most other officers Stirling looked to recruit, Mayne’s superiors were only too happy to foist him onto Stirling.

During their brief discussion in the prison cell, Stirling outlined his plan to Mayne who was very outwardly skeptical. He wasn’t entirely sure if the tall Scot standing before him was serious or even sane. Even for an unorthodox soldier like Mayne, Stirling’s ideas seemed outlandish. But like Lewes, as their conversation went on Mayne realized that he may have found an officer with whom he could work.

In Stirling’s own account of the meeting, Mayne asked him very directly, “What in fact are the prospects of fighting?” Stirling replied, “None. Except against the enemy.” Mayne thought for a moment, smiled, and said, “All right. I’ll come.”

What Mayne brought to the SAS more than anything was his edge. A quiet leader, he was pragmatic but all-around courageous if not absurdly reckless. In one incident during a nighttime sabotage mission against an Axis airfield in North Africa, Mayne had run out of bombs to plant on the planes, so not wanting to leave any enemy vehicles untouched, he leaped into the cockpit of a remaining plane and ripped out the control panel with his bare hands — not at all an easy thing to do.

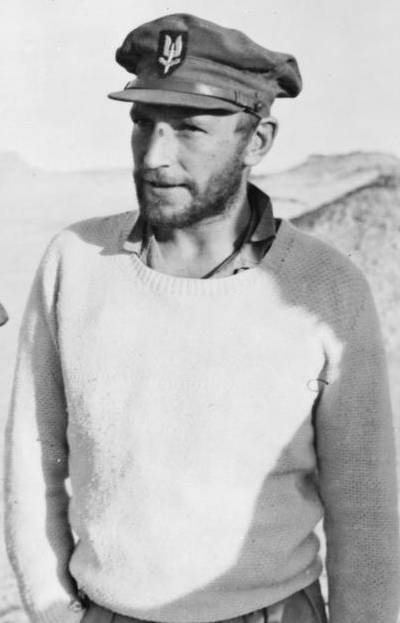

SAS legend Lt. Col. Robert Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne in the desert near Kabrit, 1942. (Imperial War Museum)

Soldiers serving with Mayne often marveled at his calm during battle and seemingly bottomless well of courage often displayed during firefights where he would run toward danger without a thought for himself to either help a comrade or complete his mission. His calm, however, like many brave soldiers was actually a deception. Inside he was as petrified as any other person in those situations. He had seen enough of war to know how fleeting the life of a soldier could be, but he also knew that a soldier’s worst enemy was panic. What Mayne had more than any other person, except perhaps Stirling, was a remarkable sense of self-control on the battlefield and during missions.

Over time the men in the SAS came to view Mayne with a quiet awe. His mere presence on a mission would give calm and confidence to the unit, possibly more so than Stirling’s. Nobody had better situational awareness than Mayne, and nobody made others around him better in the way Mayne did.

Stirling was a different type of leader than Mayne, but where the two were alike was in the way that they always led from the front. Neither ever asked soldiers to do what they themselves wouldn’t, but there was little that they would never do themselves. Neither was afraid to put himself in danger and neither was afraid to die. Their differences lay in mostly in style. Stirling was had more flair and dashing and could often inspire men with his words. He would often be the first to make an assault and did so at times in an almost cartoon-like fashion as if it never occurred to him that one of the many enemy bullets whizzing by him could actually have his name on it. Mayne was quieter and had less flair but was a more determined tactical type who gave the impression even during battle that he had control over everything including the enemy.

One former SAS operator in comparing the two leaders felt that Mayne was always focused on the immediate task and how to get the most out of a mission, whereas Stirling was always thinking of the next mission and how he could improve things the next time they carried out a similar task. That’s not to say that Stirling wasn’t focused, but he was more concerned with the bigger picture and what was next, which was the right attitude to have for a man looking to build a lasting unit-culture. Mayne, on the other hand, had the right attitude for driving performance in the field by specifically not worrying about what would come next, or how the next mission would play out. He excelled living very much in the moment and taking care of every possible variable during his operations.

If there were two things that all three men — Lewes, Mayne, and Stirling — shared was their desire to lead by example and their ability to relate to anyone of any social class or background. They could see beyond the rank, accent, or look of a person and had an uncommon collective ability to show confidence in people who were not like them.

Over those first few months in 1941, the Special Air Service under Lewes, Mayne, and Stirling trained and grew into a very capable behind-the-lines special operations force ready for action. Unfortunately, their first mission was a complete disaster.

Stirling was eager to show British Middle East Command what the new L-Detachment was capable of. Indeed he was curious himself as to whether or not his idea was sound. The opportunity to show off L-Detachment presented itself with the upcoming offensive known as Operation Crusader, whose objective was to push the German and Italian armies back from Egypt and out of Libya.

The first SAS operation was a nighttime raid in support of Crusader. Operation Squatter was the SAS airborne infiltration of two airfields behind enemy lines at Gazala and Timini. Their mission was to sabotage aircraft on the ground and divert resources away from the main British thrust, which was to begin on November 18, 1941. They would then make their way to a rendez-vous point nearby in the desert where the LRDG would pick them up.

Airborne assaults were still a new thing then, and ones done in the dark were almost unheard of. Tactics had not been Previous airborne operations including the German airborne attack on Crete had mixed results. The SAS was being very forward-thinking in doing a nighttime clandestine drop behind enemy lines.

Squatter began on the night of November 7 as 54 SAS soldiers and their equipment were packed into four planes at a Royal Air Force base in Egypt. A huge gale was blowing in over the North African coast, which made take off very bumpy and flying a hazard. Flying through a gale was dangerous enough, but trying to drop soldiers at night in a gale was close suicide. Stirling knew that they were taking a huge risk in pursuing the mission, but he felt that the unit absolutely had to make the jump in order to prove its mettle and to sway the opinion of his detractors. There had been many fits and starts with the mission and several cancellations, so Stirling felt that unless the SAS acted when they were supposed to, they would lose whatever support they had with high command.

As the planes approached their target, winds and clouds made finding the exact drop zone exceedingly difficult. When the men finally did jump — Stirling, Mayne, and Lewes were there as well — they were blown about on their decent and scattered. Some landed too close to Italian positions and were gunned down. Others were taken prisoner. One of the planes dropping them was shot down killing all aboard. Those soldiers who landed and weren’t gunned down or captured were dispersed and unable to make an attack. So they made their ways to the appointed rendezvous point with the LRDG, and ended up being pulled out without ever having hit their target. The entire mission was a disaster, for a little over half of L-Detachment was killed or taken prisoner. Stirling was deeply dismayed.

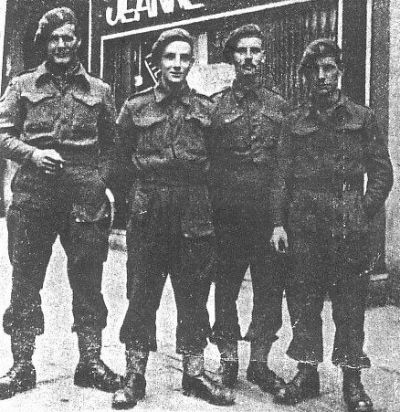

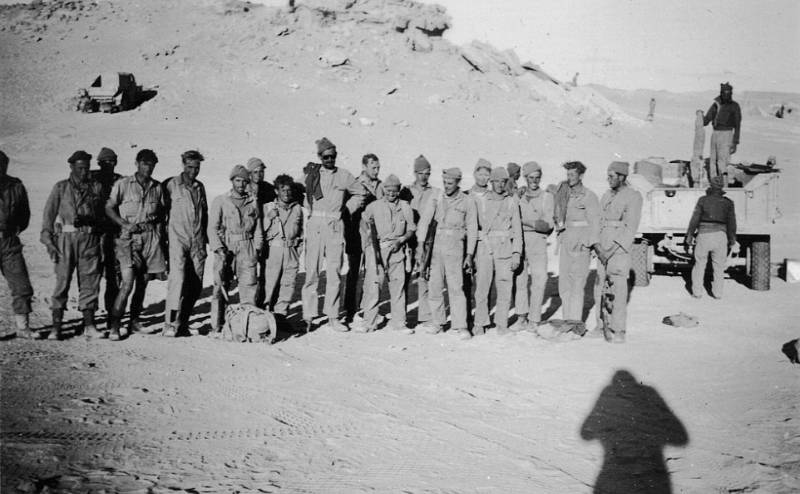

This is the only known photograph taken during the first raid ever conducted by the SAS, Operation Squatter. The person who took this photo was Captain Jake Easonsmith of the LRDG (whose shadow we see in the lower right). The tallest guy in the middle is David Stirling. To the right of him (his left), the tall guy with the sloping forehead, is Paddy Mayne. (Family of Lt. Col. Jake Easonsmith)

Lt. Col. Guy Prendergast, who was in command of the LRDG, after the mission suggested to Stirling that instead of having the SAS parachute near an objective and having the LRDG pull them out after a mission, it would be just as easy for the LRDG to actually take the SAS toward its targets in their jeeps as well as to ferry them back. At the very least it would take away some of the risk in the mission by eliminating all the unknowns that were inherent in parachuting. Stirling readily agreed and thus formed one of the most successful unit partnerships of World War II.

Their next mission in December was far more successful. With the help of the LRDG, SAS soldiers were able to sneak onto several Axis air bases, evading Italian sentries, and destroy more than 60 Axis aircraft on the ground using Lewes bombs with timed fuses. The Italians and Germans were completely surprised by the action, and were almost helpless in trying to defend their air bases from future incursions. As time went on, the LRDG trained SAS soldiers in desert navigation and driving techniques, which allowed them to come up with their own modifications for desert jeeps. Chief among those modifications was the mounting on jeep dashboards of twin-Vickers machine guns, the same ones used in fighter planes, which allowed SAS soldiers to go tear-assing around German and Italian airfields shooting up whatever targets they could acquire before slipping back into the desert under the cover of darkness as quickly as they came. Stirling even came up with a formation where a large number of jeeps equipped with machine guns could drive onto an airfield and using those guns take out the planes on the ground without ever getting out of their jeeps. At one point the SAS was responsible for destroying more Axis aircraft in North Africa than even the Royal Air Force. For the rest of the North African war, the SAS and LRDG continued to work with each other.

One of the most difficult concepts for conventional military leaders to understand about the SAS was that the types of operations it was best suited for were strategic rather than tactical. For military planners at the time, the commando unit was an easy type of unit to understand because it was essentially light infantry, which could be deployed for quick strikes and skirmishes. These types of units had existed for centuries. Like their historic predecessors, commandos were fit for tactical missions, where they would take out specific targets like a pillbox, or a gun emplacement as part of a general attack. If you wanted to take out an airfield, you would organize a raid with planes, soldiers, maybe even ships, then hit the target and either get out or hold it until the main force could arrive. Commandos, did this exceptionally well. The SAS was different but in a very subtle way. The best way to understand the relationship between the different forces is with the following analogy: if the infantry was the machete, then the commandos were the well-honed dagger, and the SAS was the scalpel; each could do the job of the other, but in the end, each has its best use scenario and training to match.

SAS soldiers jumping from steel gantries while undergoing parachute training at Kabrit, Egypt, in 1941. (Imperial War Museum)

The SAS could operate as a larger force and hit specific targets like commandos, but they were better used in much smaller formations when they could hit a series of targets and targets of opportunity far away from the battle in enemy territory. In the desert war, parties of SAS-driven jeeps and lorries would trek deep into the desert behind enemy lines, places where the enemy would not operate due to the difficulties in supply and navigation. They would hit targets of opportunity along the North African coast, then return to a forward hidden basecamp they had established to regroup and plan more missions. In this manner, the SAS hit airfields, destroyed vehicles, ammo dumps, gunned down enemy barracks, laid mines in the roads and disappeared only to do the same thing the next night. They would do this in groups of up to 100 soldiers in jeeps rolling through and shooting anything in site, or in fire squads of 3 or 4, sneaking into towns, bases, airfields, and supply dumps. They would do this night after night hitting multiple targets, sapping the enemy of resources destined for the front lines. For weeks, they would linger in the theater operating behind enemy lines for causing further erosion of the enemy supply line, compelling Germans and Italians to dedicate more soldiers to protect these “soft” installations. The more soldiers guarding rear areas, the more that were taken away from the frontlines where they were needed to fight off the surging Brits and later, Americans. Commandos simply didn’t do this. They were not intended to be deployed in the field on mission for longer than 36 hours before being pulled out or relieved. For the sake of speed, their armament was light, they carried few supplies, and they weren’t trained in long-term deployment in enemy territory.

Another aspect of the SAS role that was different from commandos was the need to be diplomatic. Especially in Greece, France, and Italy, SAS operators worked closely with local resistance groups to bleed the enemy from within, like an insurgent collective rather than as a tactical spearhead. They could operate as guerrillas and train local groups to be more effective. Commandos or other infantry units didn’t do this, nor should they have because their mission profiles didn’t require such training.

Many in the British army still didn’t see the bigger picture and often focused solely on their own immediate needs. This was apparent in 1942 when Stirling first met with the new commander of the British 8th Army, General Bernard “Monty” Montgomery. At that meeting Stirling asked Montgomery for “his best desert troops” during the final months of the North African war to conduct more raids and sabotage missions against the retreating German Afrika Corps. He argued that expanded SAS action could have a crippling effect on the enemy, possibly hastening their retreat before any organized defense could be mustered. Montgomery didn’t see things the way Stirling did and quite reasonably refused. Monty said to the brazen Stirling who had by then risen in rank to colonel, “What makes you think that you can deploy my best troops better than I can?” In his opinion, to hand over his best soldiers to the SAS would weaken the other units of his main assault.

Monty had a point, but Stirling had a slightly better one. Having the best troops in small groups hitting German targets along their line of retreat would be using their talents to their fullest and not wasting them on large-scale operations that could be handled by regular infantry using large-scale regular-infantry tactics. This could in the long run save British lives. Eventually Monty came around but it took him some time and the accounts of other officers who appreciated the SAS before he did.

To be fair to the military thinking at the time, it was always considered prudent to gather as much local firepower and manpower as possible and to mattack in force. The more soldiers attacking, the more losses the attacking army could absorb hopefully ensuring victory in what would always turn out to be a matter of attrition. The SAS way, which favored sneaking small fire teams into battle seemed according to conventional military orthodoxy at the time foolish and wasteful at best, downright idiotic at worst. Part of what made Stirling’s idea different wasn’t so much the manner of attack but the scale. Military planners didn’t see small operations as having a huge effect on battle. If an area couldn’t be held, positions taken, or enemy weakened to a high degree then what was the point? What military planners didn’t appreciate enough was the psychological effect of small-scale but numerous hit and run operations as well as the deployment of enemy manpower needed to thwart them. It takes more soldiers to guard against sabotage than it does to actually carry it out.

Military planners also didn’t realize how easy it was to throw a small wrench into the modern military machine to mess everything up for an enemy army. Tanks needed fuel, parts, ammo. Planes needed fuel, parts, ammo. Soldiers needed ammo delivered in trucks, which in turn needed fuel and parts. Take out a fuel dump with a well-place bomb. Take out a hangar with a few well-placed bombs. Take out an ammo dump with several more well-placed bombs. Take out trucks with machine guns. All of those things only required a few soldiers to carry out, but the effect they would have would be completely out of proportion to the resources dedicated toward those tasks — the SAS got a great return on investment.

Even nowadays, what would be easier? To sneak 100 guys onto an airfield, or to sneak 8 guys? For the SAS it wasn’t about taking out a specific gun emplacement or machine gun nest, it was more about bleeding the enemy army, depriving it of its precious fuel and ammunition before they could be used kill anybody. It was about instilling an uncertainty and fear in the enemy psyche, which may have been the single worst that thing the SAS did to the Germans and Italians.

After having made their mark in North Africa, the British general staff decided to expand the Special Air Service for operations in Italy, Greece, and France. Stirling’s idea had truly been realized and it was about to enter a new phase in its development. Unfortunately during those final months of the North Africa war Stirling himself got captured by the Germans during a mission in Tunisia and ended up spending the rest of the European war as a prisoner in a castle in Germany. Having lost their militarily and ideological leader, it was feared among many in the SAS that they would be turned into yet another numbered unit to be used incorrectly by unimaginative and myopic “fossilized shit” generals. Luckily for the SAS, there was still Paddy Mayne, several of the original founding members of L-Detachment, and another Stirling coming to North Africa.

British army Lt. Colonel William “Bill” Stirling was in an unenviable position in May 1943. His younger brother Lt. Colonel David Stirling had been captured by German soldiers the previous January while on a raid in Tunisia. Ranking officers in British army were looking to deploy the SAS on missions better left to other units. And Bill’s own regiment — 2SAS, the second Special Air Service regiment — was still untested and had to endure what was essentially a shunning by the remnants of 1SAS most of whom had been reorganized into the Special Raiding Squadron (SRS) and who by and large dismissed 2SAS as a bunch of soft, ineffective, green newbies.

Months earlier, Bill Stirling had been given the task of recruiting and training a new SAS regiment to build on the success of the old one, and to have them ready in time for operations in Southern Europe. On top of that, he still had to wrestle with the same general staff with whom his brother had to wrestle, a high command that did not understand the purpose of the Special Air Service, the best way to deploy them, or the type of soldier necessary to fill its ranks. Of course, there were the German and Italian armies to deal with as well — in many ways, the enemy was an easier problem to solve.

The Stirling brothers, Bill (left) and David (right). When soldiers in the regiment heard that “Colonel Bill” was going to head up 2SAS, many joked that SAS stood for “Stirling and Stirling”.

After David Stirling’s capture, the SAS was split up into a small array of acronymed units all beginning with the word “special”. There was the Special Boat Section or SBS (which actually existed prior to the SAS, and was tasked with carrying out boat-based special missions, but operated differently). There was the Special Raiding Squadron or SRS (headed by Paddy Mayne, this was essentially 1SAS but with a different name and was filled with SAS veterans). Then there was the newly formed 2SAS, which was made up almost entirely of new SAS soldiers. Also formed were the French 3 and 4 SAS, Belgian 5SAS, and Dutch 6SAS, all made up of free recruits from those countries and trained by British SAS operators.

The second SAS, or 2SAS was officially formed in May 1943, and was based in Philippeville (present-day Skikda), Tunisia. This was an unfortunate location to have been given because Philippeville was located near a mosquito-ridden swamp teeming with malaria. By the time 2SAS was ready for deployment, more than half its members would had been in hospital with the disease, unable to carry out missions. For many, they would carry the disease for the rest of the war.

Bill and his brother shared a similar military background. Both were Lieutenant Colonels and both had trained and served as commandos. They also shared a strong opinion in the best way to deploy the SAS. The biggest way they were alike was that neither had any affinity for the military brass. Unlike David, however, Bill wasn’t a natural lead-from-the-front type of soldier. A good leader in his own way who had the affection of many of those under him, Bill far was more reserved and cerebral. Bill spent more time in his head trying to work out every possible detail of action before sending his men out into the field, wheras David was a little more hands-on and willing to let the action dictate the plan to a degree. Bill also possessed a better knack for dealing with the boundless bureaucracy of the army than his brother did. Until the very end of his tenure as commander of 2SAS, Bill was able to smooth relations with some in the military and actually work within the military structure quite effectively.

As a leader Bill had a firm grasp of his strengths and being a field operator was not one of them. During his whole period as commander of 2SAS, Bill never once went out on a mission, which was a good thing really and did not at all take away from the respect his men or other SAS operators held for him. David, on the other hand, before he was captured, not only went out on dangerous missions but insisted on driving his own attack jeep.

When it came to dealing with the men, David and Bill both possessed the ability to find common ground with anyone and converse about anything, which made them very popular. By many accounts Bill was a very likable person, but he didn’t possess the same disarming charisma of his younger brother who could often sway people simply with his manner of conversation. But probably the biggest similarity in their leadership styles, and one that drove both to perform perhaps more than any single motivation, was their absolute devotion to the men under them. Both Stirlings worked tirelessly to ensure their men were put in the best possible position to succeed and defended their interests passionately whenever higher-up planners ever tried to misuse them. This drive would later cost Colonel Bill command of his regiment, but it was also essential in building on the culture first establised by his brother, Mayne, and Lewes.

With a wealth of operational experience to go on, 2SAS from the beginning functioned more as a fully formed unit with specific and measurable standards. The new unit benefitted specifically during its formation from the experiences of L-Detachment, the Special Boat Service, the LRDG, and the commandos. Whereas his brother often times improvised in his recruitment, Bill Stirling and the heads of the special warfare unit had a better idea of the type of soldier they were looking for and the types of situations they’d be getting into. There was less feeling around in the dark and more hand-picking of qualified men. There was also more formality to the whole endeavor — it was less freewheeling as it was during the desert campaign. From the beginning 2SAS had far less freedom to develop as they pleased, however, the more rigid standards put in-place were ones that were built on and codified from the standards of L-Detachment.

One thing 2SAS had to endure that L-Detachment didn’t as much was the lack of quality soldiers fit for SAS duty. Then as they do today, the SAS needs a certain type of soldier in order to function properly — one who is self-motivated, mentally and physically tough, and one who can see situational possibilities and solutions where others cannot. By the time 1943 rolled around, there were few commanding officers in combat units willing to let their best soldiers be transferred to the SAS. This made things even more difficult for Bill Stirling as he was also feeling competition for soldiers from Mayne’s SRS/1SAS. In addition, there was feeling among many officers in the British army that the SAS was no longer necessary especially since the war in the desert had ended and there wasn’t a need for anybody to go tooling around in souped-up jeeps anymore. When David Stirling set out to build the SAS, the lack of understanding of what he was building almost helped him in recruiting soldiers since other officers had nothing yet to criticize. In what was and continues to be an ironic hindrance for the SAS is their own intense secrecy and modesty works against them, especially when others are trying to assess their impact in a given theater or situation. When it came to recruiting soldiers to SAS or even keeping the unit alive, other officers for lack of knowledge could make the case that the whole SAS thing was indeed a fruitless endeavor. Of course they were wrong.

For manpower, David had almost the entirety of Layforce to draw from, which was itself an elite commando unit. Bill Stirling was able to draw from his old commando unit, but unlike David’s Layforce, Bill’s old unit was still fighting and the officers in that unit resisted his recruitment.

The selection process for 2SAS was more test-driven than that of it’s elder sibling unit. For one thing, the selection process for 1SAS was often little more than David Stirling asking candidates a few questions. If he thought them fit he would send them out on his grueling training course to see if they could keep up. Those that didn’t were sent packing back to their units. 2SAS on the other hand had a more structured process of selection and interview, which included long timed runs up hills. If they made it past that next came weapons training, demolitions training, parachute training, constant evaluation by SAS vets, not to mention physical training up the wazoo. For 2SAS, the selection process looked far more like today’s 22 SAS selection than it did to L-Detachment/1SAS selection, except it was done in a shorter timespan.

The greatest and most lasting effect of the development of 2SAS on future SAS as a whole was that it didn’t need the combined personalities of David Stirling, Mayne, and Lewes to push it along. Instead 2SAS relied on the young but established SAS culture and experience to guide its formation and influence its operation. In that sense, if 1SAS (from its days as ‘L-Detachment’) was the prototype, 2SAS was the finished product, the one that could be replicated and reproduced — the model for all future SAS selection, operation, and training. It was no longer “Stirling’s Private Army”, but a full-on top-to-bottom British special operations force with hard, specific standards and training — the absolute realization of the concept.

The very first operations conducted by 2SAS were small-scale jeep raids in Tunisia ahead of U.S. First Army’s advance from the west. More like recon exercises than actual missions, these small raids together composed the entirety of 2SAS’s North African operations. It wasn’t until they began operation in the Mediterranean before 2SAS experienced the full agony of their growing pains.

There’s no other way to put it, those first operations conducted by the new SAS unit in the Mediterranean were abysmal. The operators themselves seemed downright incompetent especially when compared to their predecessor unit. But it really wasn’t simple incompetence that was the problem with 2SAS, there was a fair bit of bad luck.

The HMS Safari submarine was used to to bring SAS operators to Sardinia during Operation Marigold. The mission was a complete failure, but the sub itself did fine.

Marigold

One of the unit’s first operations involved landing a small team of 11 operators on Sardinia where they hoped to take prisoner one of the soldiers in the Italian garrison for interrogation. Known as operation Marigold, the mission was a ridiculous fiasco from the get-go.

Marigold took place on a dark night in May 1943. The HMS Safari — a British submarine — took the operators as close as they could to their beach landing zone before surfacing to allow the raiders to disembark. The men loaded themselves into inflatable dinghies and began to paddle toward the shore. Things soon started going wrong.

The first issue was the wind, which was blowing northwards and pulling the dinghies away from the beach. The operators compensated by trying to row against the wind, but it made the trip take far longer than they had originally planned — one and a half hours instead of a half hour. When they finally made it to shore, they realized that they were very much behind schedule. So to save time and get to their objective quicker, the operators decided to keep their dinghies inflated on the beach instead of deflating and hiding them. This could have easily come back to bite the operators in their collective butts, but according to Harry “Tank” Challenor, one of the SAS operators present, that decision probably saved their lives.

With all the stealth and tact they had spent weeks training to perfect, the team made their way up the bluff trying in vain to lessen the sounds of their footsteps over the loose and noisy shale. As their luck continued its downward trajectory, one of the men, a private, accidentally dropped his weapon onto the rocky ground, which made a very loud sound. According to those who were present, the loud clack of the gun hitting the ground seemed to echo up and down the landing. It was only a brief moment later that an Italian machine gun from out of the darkness opened fire on the tired SAS lads, who were caught in the open on the difficult-to-maneuver-over shale bluff. The almost complete darkness was swept away by a flair sent up by the Italians that lit up the whole beach. The operators returned fire and quickly scattered in different directions ultimately running back to their dinghies still inflated on the beach. Challenor and three other men got into one dinghy and began paddling as fast as they could out into the night blackened sea. In what seems like a scene from a dark comedy, Challenor realized that their boat was circling around because one of the other operators got into the boat facing the wrong way with his back to the others, and was paddling against them. Upon realizing this, all the men in the boat got up and turned around, including the one who was turned around in the first place, so the whole crew ended up back in the same position they were in before paddling against one another. After several more tense moments with Italian machine gun fire zipping into the water around them, the men finally righted themselves and began paddling out to sea. The machine gun fire stopped as the operators slipped into the darkness.

Things seemed to be going better for Challenor’s boat until one the men noticed their dinghy seemed bigger than it was when they first got in. That is, it seemed to be inflating more. In the rush to get out to sea, one of the men had inadvertently hit the inflate valve, which began overfilling their boat with air. The team was away from the shore and covered by the darkness, so believing they were a safe distance out, they tried to let out some air to prevent the boat from bursting. In doing so, the valve let out a very loud high-pitched squeal, which again drew machine gun fire from the shore.

In the end, most of the raiding force made it back to the sub, all except one who went missing during the operation. Despite the loss of a comrade, the surviving operators had a dark chuckle over the absurdity of their ultimately fruitless and wasteful mission.

Snapdragon

A similar operation took place on Pantelleria, a small rocky island halfway between Tunisia and Sicily in a very strategic location. This island had been a problem for the British since the early days of the North African war when they had attempted to take the island over but were repelled by Axis aircraft and the huge artillery guns that were mounted on the island. In advance of their upcoming invasion of Sicily, Allied Command decided it was imperative they subdue the island along with its 10,000-strong garrison. Lacking any concrete information about the island defenses, a team from 2SAS was tasked with sneaking onto the island, taking a prisoner, and bringing him back for interrogation. The mission was called operation Snapdragon.

Unlike Marigold, the raiders had little trouble leaving the sub getting onto the island. They even managed to quietly and efficiently scale a steep cliff that overlooked the sea, which at night is a very difficult and dangerous thing to do. At the top, the operators found an Italian soldier who luckily was on guard duty all alone with nobody else nearby. The SAS operators easily captured the very surprised guard and secured him for the trip back down to their dinghies. All seemed to be going well until they began making their way down that steep dangerous cliff. Details of the operation vary, but the operators accidentally dropped the Italian soldier who then fell to the bottom of the cliff breaking his neck. The mission ended with the raiders heading back out to sea empty-handed and an unlucky Italian guy dead at the base of a cliff.

(As a side note, the island was later reconnoitered by air and sea and was taken over by British forces after a horrific bombardment where the RAF dropped upwards of 4 tons of explosives on the garrison, which complimented a large naval bombardment from British ships.)

There was another separate mission taken up by 2SAS to take out a radar station nearby on another small island between Tunisia and Sicily. Of course, it being a radar station, the Italians knew the British were coming because they were alerted to the British presence by that very same radar — an event whose possibility hadn’t occurred to the planners of the mission. As the boats of operators came within range of the shore, a flare went up and machine guns blasted. There were no casualties as the men of 2SAS turned about and headed back to their sub.

Chestnut

What really didn’t help things for 2SAS was an operation in Sicily where two teams were to be dropped into the northern part of the island to take out German and Italian supply dumps and to prevent the Germans from containing the allied landings on the southeastern portion of the island. Bill Stirling himself had advocated for such a mission because it was the type of operation that he, like his brother, felt was the true purpose of the SAS. In a memo he issued to Allied Command, Bill suggested dropping 140 men from 2SAS over a large area in northern Sicily, where they would disperse in fireteams of 2 to 4 and harass the Axis supply lines in any way they could. Knowing his commanders’ reluctance to perform such an airborne operation given the debacle of Operation Squatter, Bill stated clearly that his unit was quite willing to undertake an un-reconnoitered nighttime parachute drop despite the dangers. Allied command was sold on the idea, but not on the scale. They decided that only two teams of 10 men each would drop into northern Sicily, and would be supported by about 40 more 2SAS operators who would arrive later. This mission was named Chestnut.

The drop took place on the evening of July 12, 1943, and it did not go well at all. One of the teams was scattered during their drop while the other landed too near to a town that had a heavy German presence. What was worse was that nearly all their equipment including their radios were lost, which meant they couldn’t contact their headquarters with requests for reinforcement and resupply. Several operators were eventually captured while the others, not able to conduct any meaningful sabotage missions without their equipment, made their way toward the advancing allied lines. Lastly, one of the transport planes that carried the force toward its drop zone was lost on the way back.

Not all was bad for 2SAS in Sicily however. One bright spot for the unit came on the eve of Operation Husky, the allied invasion of Sicily. A small group of operators from 2SAS was attached to SRS in a mission to take and hold a lighthouse on the southeastern coast of the island, which had a commanding view of the landing beaches. It was also believed to house several machine gun nests that would have made the landing more difficult.

The operators launched from their transport ship into choppy waters on the evening of July 9 in small dinghies. Making their way onto land, the operators maneuvered toward the lighthouse only to find that the place was deserted. Although the mission was carried out flawlessly, it didn’t exactly prove anything about 2SAS or do much to improve its reputation within Special Operations.

Given their early setbacks it was no wonder that Paddy Mayne and the operators of 1SAS/SRS looked down on the newbies of 2SAS. While 2SAS was fumbling about trying to establish themselves, 1SAS/SRS was splitting their time between training in the eastern Mediterranean and conducting successful recon and raiding missions. Like any close-knit group, for many of the original soldiers of L-Detachment it was almost galling to see this group of 2SAS “amateurs” trying to play the role of clandestine soldier. The newcomers weren’t there for the early raids on the airfields in Libya. They weren’t trained by David Stirling or Paddy Mayne. They weren’t the men who helped turn the tide in the North African war.

What the newcomers were, however, was the next step in the evolution of the force. The early troubles of 2SAS weren’t any worse than those of L-Detachment in its early days. Even though 2SAS had many advantages over 1SAS, chiefly among them the training that was based on L-Detachment’s experience, much of what had to be learned had to be learned in the field. 1SAS in many ways had the luxury of obscurity — nobody knew what they were doing, but better yet, not many heard of their failures. 2SAS on the other hand had to face scrutiny from the same non-believers who plagued 1SAS, and 1SAS itself.

Operations in Italy began in earnest in 1943. If it was in the desert where 1SAS became a dangerous force, it was Italy was where 2SAS as a unit came into its own.

Three heavily armed members of 2SAS, draped with ammunition belts and each carrying components of a Vickers heavy machine gun, climb a mountain path as they go out on an operation to assist Italian partisans in the Castino area of northern Italy, 1945. (Imperial War Museum)

British 8th army had invaded the Italian mainland on September 3, 1943, and in support of this invasion, 2SAS figured heavily in both the south and north of Italy. The situation in Italy itself was very fluid as the Italian government formally announced an armistice with the allies on September 8. The Germans, however, were not about to let Italy fall into the hands of the Allies so they ended up taking over the country’s defense. Over the next two years some of the fiercest fighting in the war took place in there. Because of the mountainous terrain, the ideas of blitzkrieg and maneuver warfare were set aside for WWI-style artillery and trench warfare.

In support of the Allied landings at Calabria and Salerno, five squadrons from 2SAS landed at Taranto on September 10 to seize the port and harass any retreating Italian and German troops who were heading north. Little was known about what sort of resistance they would encounter, which was a major cause for concern for not only 2SAS but for the entire invasion force. Luckily for 2SAS, it was a relatively easy operation as they were able to push aside the tiny garrison of Italian defenders quickly. With little resistance, several squadrons of 2SAS were ordered to push inland, scout out the rugged terrain around Taranto, and harass any hostiles they came across.

D Squadron of 2SAS headed toward Bari in their modified jeeps looking for any German or Italian partisan resistance. Along their way, the squadron came upon a bridge defended by a small group of skittish Italian soldiers. One of the operators got out to go talk to the Italians, but before he got very far, the Italians opened fire barely missing him. The rest of D Squadron returned fire killing one of the Italians. After a very short exchange, the Italians put down their weapons and surrendered when they realized they were shooting at British. Apparently, the Italians thought they were facing fascist guerrillas who did not accept Italy’s surrender and were determined to stand by their German allies. In the end the Italians apologized to the Brits and cooperated with the operators giving them information on the situation in the surrounding area.

A day later, D Squadron came upon a very unlucky German column that was heading north and east away from the Allied beachhead. According to first-hand accounts of the skirmish that took place, the 2SAS operators took up hidden positions on either side of the road over which the Germans were traveling. As the column passed by, the operators opened fire completely surprising the German soldiers. In the final tally of the skirmish, the operators took out 10 German vehicles, killed at least 6 soldiers, and captured 42.

On another patrol, 2SAS operators came across the jarring sight of a concentration camp — the first that any of them had seen. The camp housed mostly Italian political prisoners, who were malnourished, emaciated, and filthy. Although there had been reports of such place, it was still a shock to the men. Many prisoners would not come out from their cabins either because they were too weak or they were worried it was a trick by their captors. When the camp was secured, the remaining guards were rounded up by the SAS operators and in a reversal of fortunes, the guards were placed under the care of their former prisoners. The scouting patrol went on their way when satisfied that the camp was fully liberated, but the image of the prisoners and the conditions they lived under stayed with the operators who were not prepared for such a sight.

As the camp was being liberated, other SAS patrols were still going on. In one instance that could have ended up a tragedy, a group of 14 operators came across an automobile tunnel under a hill. Two operators were left at the entrance in case any Germans should come up behind them, the other 12 went in to scout the tunnel. As time passed, the two soldiers left to guard the tunnel thought it a great opportunity to go find a tavern to get a drink. Believing they were in a quiet sector they left their post — in the middle of an invasion — to go have a pint.

While the witless soldiers were off seeking a tavern, elements of a German battalion came driving through the tunnel where the two guards were supposed to be. Luckily the other 12 SAS operators were able to avoid detection but only barely. Once the column passed and the SAS patrol returned, the two shirkers were exposed for having left their post and by the next day, they were kicked out of the SAS and sent back to their regular infantry units.

There were other skirmishes fought during this time between elements of 2SAS and the German army, all the while ecstatic Italians who were tired of war came out and cheered the British soldiers in some places where they went through. All in all, it was a good showing for 2SAS.

Jonquil and Begonia

After several more scouting forays, 2SAS was ordered back to Bari to take part in operations Jonquil and Begonia — joint operations whose main goals were to ferry liberated British POWs from their camps in Italy to the sea where they would be picked up by the navy near Termoli. The POWs had been freed with Italy’s surrender and were themselves in a precarious position with German troops hunting down any who escaped.

As the plan was laid out, several squadrons from 2SAS and SRS were to make beach landings up the east coast of Italy to meet up with freed prisoners. In the parallel operation, a detachment of 200 commandos would drop in behind the frontline to help round up the prisoners, take out any German resistance, and bring the POWs to the coast. Those POWs would then be ferried to Termoli where D Squadron of 2SAS provided area security.

Unfortunately the plan never fully came together partly because of poor planning but also because of German action around Termoli. By the end of the operation which took place throughout October and November, very few of the prisoners were rescued. At headquarters, the mission was considered a failure, which irked Bill Stirling, who faulted the staff officers who planned the mission. He felt that the mission was a failure because neither he nor anyone from 2SAS was consulted on the planning. Furthermore, he felt it was yet another misuse of the SAS. Fortunately, another group of 2SAS men had better luck. As part of the Jonquil mission they landed about 50 miles north of Termoli on October 27 and took out many elite German SS soldiers over the next few months. The group ended up being a thorn in the side of the German army in southern Italy until January when they returned to allied lines.

Termoli

The Battle of Termoli was a significant event in the history of 2SAS as it was the first time that they fought alongside 1SAS (as SRS) in a full-on armed confrontation. In support of 8th army’s invasion of Italy, the SRS (1SAS) with Mayne in charge along with a combined force from No. 3 Commando and No. 40 Royal Marine Commando — altogether a force of 207 men — were tasked with taking and holding Termoli, a port city on the southeast coast of Italy. Termoli was far to the north of the main body of British army or any of the American units operating around Salerno. It was to be used as a base for further SRS incursions along the Adriatic coast as the main Allied force pushed up the Italian peninsula. It was also supposed to be the evacuation point for British POWs secured in operations Jonquil and Begonia. The British hit Termoli from the sea on October 3, completely surprising the German garrison, which did not expect a seaborne assault to take place in their sector. The invasion force was able subdue the town later that day after fierce building-to-building fighting, but the situation in town was precarious and fluid.