We’re not as arrogant as those gold medalists!

07/27/2017

Updated on 10/21/2022

Madison Square Garden is New York’s premier indoor arena and venue. It is the home of the the New York Knicks (NBA), the New York Liberty (WNBA), and the New York Rangers (NHL) sports franchises. It is the main venue for the Men’s Big East Basketball Conference Tournament, the National Invitational Tournament Final and many other sporting and boxing events. Even the first Wrestlemania was held there. As a concert hall, many famous bands and musicians have performed there, including Aerosmith, Marc Anthony, Beyoncé, Black Sabbath, Cher, Eric Clapton, Depeche Mode, Bob Dylan, Missy Elliot, Enrique Iglesias, Janet Jackson, Michael Jackson, Billy Joel, Elton John, Alicia Keys, Kiss, Lenny Kravitz, Lady Gaga, John Lennon, Madonna, Metallica, Katy Perry, Phish, Elvis Presley, Prince, the Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, Barbara Streisand, Taylor Swift, U2, Kanye West, Whitney Houston, the Who, Neil Young, and many others. Famous comedians such as Aziz Ansari, Dave Chappelle, and Jerry Seinfeld have played there. It was the site of the 2004 Republican National Convention. Baruch College, the New York Police Academy, and Yeshiva University hold their commencement proceedings there. The Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show is held there every year. Truck pulls, conventions, circuses — pretty much any major New York event that requires a large indoor venue finds its way into Madison Square Garden.

Located on a two-street-block area between 32nd and 34th Streets and 7th and 8th Avenues in New York on top of the New York Pennsylvania Railway Station (Penn Station), the Garden is not actually on Madison Square as the name would suggest, but about 4 avenue blocks west and 6 streets north of its original location on the square from which it gets its name. In all, there have been four Madison Square Gardens built in three different locations, the first two on the northeast corner of Madison Square, the third on 8th Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets, and the fourth where it stands today.

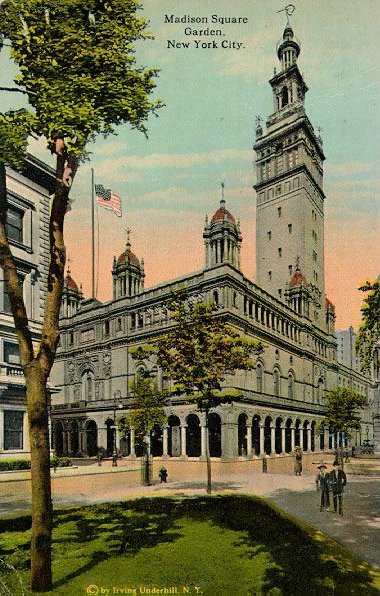

As a building, the current Madison Square Garden from the outside is a bland, hockey-puck-shaped structure. Sure, on the inside it’s an okay place to watch a game or to see a show, but on the outside it represents all that was bad with mid-20th Century American architecture. What is particularly galling about the current Garden is that it replaced a far more architecturally appealing structure, the former New York Penn Station building, which was torn down in 1968 to make way for the characterless eyesore that sits there today. The Garden before the current one wasn’t exactly a beautiful work of art, but at least it had a bit more character and didn’t come at the expense of a dilapidated yet beloved and iconic building. It’s true that Madison Square Garden never needed to be anything more than a building built to serve its function and purpose, most venues today are like that, but one exception in the history of Madison Square Garden was the arena’s second incarnation. Built in 1890, it was by far the most extravagant of the four “Gardens”. Designed by one of America’s greatest (and most disgustingly lecherous) architects, the second Garden building was not just a venue but an architectural landmark and a triumph of Gilded Age New York until it was unceremoniously demolished in 1925 to make way for an insurance company’s headquarters.

The story of the second Madison Square Garden begins with the first Madison Square Garden, which opened in 1871.

This is what the first Madison Square Garden looked like. Aside from the fact that it probably smelled terrible, even for New York, the biggest problem with the first Garden was that it didn’t have a roof, so it couldn’t be used in the winter or during rain storms.

The site of the first Madison Square Garden was on the northeast corner of Madison Square Park where Madison Avenue meets the Square at 26th Street. Originally, the site was a railroad depot on the New York and Harlem Line owned by the Vanderbilt family. Steam trains weren’t allowed to go below 23rd street in that part of Manhattan, so the depot functioned as a sort of transfer facility from train to horse & carriage. It was a dirty sooty place that reeked of smoke and horse shit, something that contemporary New Yorkers would not associate with present-day Madison Square.

With a large, open, former depot on his hands, Cornelius Vanderbilt decided in 1871 to lease the land and building to the great American showman and con man P.T. Barnum. Calling the former depot “The Great Roman Hippodrome”, Barnum turned the building into a large open-air venue where he erected a huge tent over the performance area and would put on his circus shows along with sporting events and other great spectaculars.

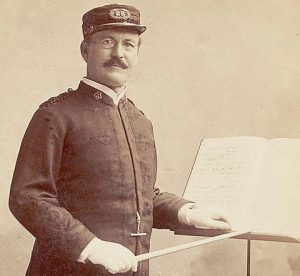

As time went by and Barnum’s attentions went elsewhere, Vanderbilt in 1876 leased the arena to the then well-known, Irish-born, bandleader and composer Patrick Gilmore.

Gilmore had conducted several bands before serving in a Massachusetts regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. After the war, he was asked by the U.S. Army to help reinstate and reform the Army band. Afterwards Gilmore conducted his own bands in front of many large gatherings, which made him a celebrity. As historic figures go, Gilmore is one of those personalities whom most people today have never heard of, but he made several indelible contributions to American culture that we recognize today: he is credited for penning the lyrics to “When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again“; he established the yearly tradition of a big band playing a 4th of July concert in Boston, a tradition that was taken up by the Boston Pops; and his was one of the first bands that Thomas Edison recorded using his early recording devices.

Patrick Gilmore was a well-known bandleader who was the first to call the arena a “Garden”, when he named his venue Gilmore’s Concert Garden.

After leasing the Hippodrome, Gilmore changed the arena’s name to Gilmore’s Concert Garden — alluding to pleasure gardens, which were open public spaces in cities where concerts and shows were performed. He began to not only hold concerts for his own band, but he also booked a variety of entertainments and other events in the space, such as bicycle races, temperance meetings, dog shows including the very first Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show, and trade shows. Building on Barnum’s successes and uses of the space, the Garden’s popularity grew, but it had some drawbacks that prevented Gilmore and later promoters from really cashing in on the space.

Because it was an open-air venue, Gilmore’s Garden was limited by the elements. New York gets really cold in the winter and really hot in the summer, both conditions with which Garden customers did not want to put up. They also weren’t too keen on sitting in the rain or snow either. Tents over the venue helped greatly in the summer, but not in the winter, so events could not be held. In addition, the building itself was showing its age and in need of repairs. This put a real strain on the Garden’s finances, making it a very difficult place to turn a profit.

When Cornelius Vanderbilt died in 1877 his grandson William Vanderbilt assumed control over the Hippodrome. In 1879, Vanderbilt officially changed the name of the arena to “Madison Square Garden”, turning the name into a brand that would stick around into the present. Over the next few years, however, Vanderbilt found the Garden to be as troubling as his grandfather did. He tried to push sport as the venue’s main revenue stream, especially boxing matches as those seemed to draw the biggest audiences. But by that time the city cracked down on the sport and left Vanderbilt with a shabby, profitless, building, minus its strongest potential revenue source. Quite understandably, he wanted out.

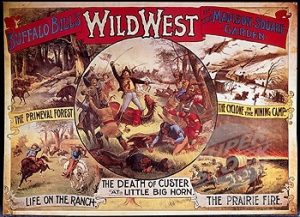

One of the most famous American shows to play at both the first and second Madison Square Garden was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. Those shows, which Bill Cody toured with in the U.S. and Europe for over 30 years, gave guests a glimpse of the American West, albeit a highly fictionalized version of it. For many people, these were the only Native Americans they’d ever seen, other than ridiculous and racist depictions in the press. This poster is from 1883.

Although Madison Square Garden had not been very profitable up to that point, the idea of a grand city arena was an attractive one to a group of investors that included robber barons such as William Waldorf Astor, Andrew Carnegie, and J.P. Morgan, and it was to this group in 1885 that Vanderbilt sold the site and the business. This group not only wanted to turn a profit on the endeavor, they also wanted to create a venue out of Madison Square Garden befitting the great American city, putting it on par with London, Paris, and Berlin. In Madison Square, they saw tremendous potential.

Although the venue had never been profitable, it wasn’t as stupid of an idea as it may seem now to build a new one on the same spot. Back then, the Madison Square area was hopping with dozens of restaurants, theaters, and clubs all nearby. When people went out at night, often times it was to the Madison Square area, which meant that there was a lot of foot traffic going through. Given the right enticement, that foot traffic could be turned into paying customers. So the investors decided to tear down the old Garden and build a new venue to create that enticement. To accomplish this, they hired the well-known architecture firm of McKim, Mead, and White to design the new building to put over the site. It ended up being Stanford White, a partner in the firm, who would design it.

Stanford White was one of America’s most widely known architects and is today considered an important figure in U.S. architectural history. A minor celebrity during his time, White and his firm designed some of the most striking and noteworthy buildings of the Gilded Age and after, including: Villard Houses (1884); All View estate (1890); Washington Square Arch (1892); the Bowery Savings Bank (1895); the Battle Monument at West Point, NY (1897); Judson Memorial Church (1888); Rosecliff (1899); Seaman-Brush House (1899); Gould Memorial Library (1903); Tiffany & Co. Building (1905); Trinity Episcopal Church, Roslyn, NY (1906).

White was tasked with creating a new venue befitting the increasingly cosmopolitan New York City, and create one he did. Far surpassing both expectations and the budget he was given, White’s Garden was unlike the previous in almost every way. It was ornate, sophisticated, functional, contemporary, beautiful — the building would eventually be considered one of White’s greatest achievements. Of all the four buildings to call themselves Madison Square Garden, White’s was the most majestic.

Madison Square Garden from what was then 4th Avenue (present-day Park Avenue South). Madison Square Park is on the other side of the building.

The second Madison Square Garden was an extraordinary expression of contemporary tastes and aesthetics. Fantastic as well as fantastically big, the Garden as a whole took up an entire city block and had several performance spaces built into its structure. The exterior was a very of-its-period Beaux-Arts facade with columns, arches, archways, and spires. The defining feature of the exterior was a single 32-story bell tower that stood above everything else like a minaret in the Moorish style. White based the design of the tower on that of the bell tower of the Cathedral of Seville in Spain, the Giralda, which was also built with Moorish features and themes. Within the Garden’s tower was an elevator, stairs, observation decks, and apartments, one of which was occupied by Stanford White himself. On the ground floor, a space was created for a large restaurant to occupy, which opened out onto 26th street. The entrance to the main hall of the Garden was on the east side of the building on 4th Avenue (present-day Park Avenue South).

The interior was very fancy and ornate. All the staircases were made of marble and the pillars in the lobby and hall areas were all of polished granite. The floors were patterned stone mosaics, and the walls in some places had marble columns built into them. The Garden’s main hall was huge for the time, measuring about 70,000 sq. ft. (about 6,500m) with a ceiling that rose 80-ft. (about 24.4m) from the floor. The space could easily accommodate large functions, shows, and conventions, while also having enough modularity to reconfigure the space for other types of shows and sporting events. The space could seat about 10,000 guests easily with a further 4,000 standing. Behind the upper balconies were windows to allow for circulation, which, given the crowds the building was designed to hold, were very important. Additionally, a part of the ceiling could be mechanically opened to create a skylight and allow heat to dissipate, thus enhancing airflow. It also allowed for natural light to shine down on the main arena floor under favorable conditions.

There was also the smaller amphitheater which could accommodate several hundred guests with its entrance near the corner facing Madison Square Park. It was a very elegant theater with a large stage framed with ornamental moulding and coffering around and about the arch above the stage. The whole amphitheater for that matter was covered with ornamental moulding according to White’s meticulous standards. In accordance with the best-practices in contemporary acoustics, the theater and the main hall were engineered to provide the best possible spaces for sound to travel.

One of the coolest features was the rooftop restaurant and theater. These rooftop theaters were a bit of a trend in New York at the time and the Garden’s was among the most celebrated. At the Garden Rooftop Theater, guests could dine al fresco beneath hanging lanterns while enjoying a play or a musical performance. It was here at the Garden Rooftop Theater where White met his end in 1906 when he was shot in the face by an insane man who harbored a tremendous amount of jealousy and hatred toward White. (More on that story below.)

In Madison Square Garden, White had truly built a masterpiece, an event venue that stood above all others in New York. To much fanfare, the new Madison Square Garden opened in 1890 with thousands flocking to it in its first few months of operation. For the time it stood, it was one of New York’s most celebrated buildings.

(Have a look at image gallery at the bottom of this page to see more images of the interior and exterior of this lovely building.)

One of the signature features of White’s Madison Square Garden was the statue of Diana that stood atop the main tower. Designed by the famous American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudins, the gilded statue depicted the naked Greek goddess Diana standing on her front foot pulling back an arrow as if to fire. White, who was a friend of Saint-Gaudins and with whom he had worked on several statues and monuments, convinced the artist to design the statue at no cost. Saint-Gaudins agreed, and, using two models (one for the body, and one who happened to be his mistress as the face), he created the iconic statue. Not only was it a beautiful piece of artwork, Diana was designed to function as a weathervane rotating at its base in the direction of the blowing wind. Saint-Gaudins sculpture was very much the finishing touch White wanted for his creation. There were, however, four problems with Diana.

Above is the second version of Saint-Gaudins’ Diana soon after it was installed in November 1893. The copper drapery, or foulard as the fancy people call it, was attached to the statue in an effort to make it less naked, thereby shutting up all the prudish New Yorkers who were offended by her nakedness.

The first problem was more of an engineering issue. The statue was 18 ft. tall and weighed almost a ton (1,800 lbs. to be precise). There was no wind anywhere that could move it so the whole weathervane thing was out.

The second problem was with the way the statue was cast. When the men at the foundry went to cast the sculpture in accordance with Saint-Gaudins’ specifications, due to the size and weight of the statue they found that the main supporting rod, which was originally supposed to go in through the statue’s toes on her left foot and straight up through the leg to the body, wouldn’t work. It would have made the piece unstable and likely to break at the thigh. So the guys at the foundry decided to put the rod through Diana’s left heel instead, which made it look a little weird, at least up close. This wasn’t honestly a terrible problem for viewers on the ground who were a ways away from the sculpture, but it really got under the skin of the very particular White and Saint-Gaudins.

The third problem was that White and Saint-Gaudins kind of messed up the proportions of the statue when they put together the specs of the piece. After its installation on top of the tower, Diana looked enormous and completely out of scale with the rest of the tower and building, almost cumbersome. For the two visually driven artists involved, this was a huge no-no. So at their own expense and after a little under a year atop the tower, White and Saint-Gaudins had the statue removed. To replace it Saint-Gaudins created a newer, slimmer, shorter version of Diana, that in many ways was more elegant than the first. When this one was cast, the statue would be attached to its base on the figure’s toes as Saint-Gaudins originally wanted, plus it was light enough to turn in the direction of the wind. A gleaming figure as well, White designed a series of gas and electric lights to shine up at the statue giving it a glow that could be seen for miles. This brings us to the fourth problem.

The figure of Diana was lithe, athletic, and very naked, which caused a bit of a stir in those sexually repressed times. Even though it was a fine work of art, some of the contemporaries of the day objected to having a gleaming statue of a naked woman up there for all to see. There were even accounts of men staring at the statue through telescopes to get a look at the naked figure — a pathetic form of pornography of yestercentury. To shut up all the naysayers, prudes, and other squares of the day, White asked Saint-Gaudins to attach a sort of metal drapery onto the new statue in an effort to obscure Diana’s figure and privates somewhat. Of course, that solution only lasted a short while as the fierce New York winds made quick work of the drapery knocking it completely off Diana only a few months after it was installed. As time went on, the people who were against the statue became fewer, and the feelings of moralistic outrage and Victorian prudishness died down.

Like its predecessor, the main amphitheater of Madison Square Garden played host to many different types of shows, events, and other entertainments. Because of its size, the Garden provided a venue for many of the same entertainments in the late 19th century that the current MSG does today.

Here’s what Madison Square looked like in 1893 from the southwest side of the park looking northeast. The tower of Madison Square Garden is seen standing prominently above the other buildings. This would quickly change over the next 25 years as skyscrapers went up around the popular venue. (New York Public Library).

Sporting events were pretty common at the arena. They included cycling races, horse shows, hockey matches, and wrestling. In 1902, the first ever indoor American football games were held at the Garden. This must have been quite the site in those days when the game was far more violent and dangerous than it is today, not to mention the fact that the Madison Square Garden floor wasn’t exactly soft and forgiving. Known as the “World Series of Pro Football”, two of these tournaments were held in the Garden.

Other sporting events in the garden were less sweaty and bloody. In 1909, 24 bowling alleys were constructed in the main arena, which took up the entire floor of the amphitheater for the National Bowling Association Championship. To service the alleys were numerous pin boys who would set up and remove fallen pins. These tournaments took place several decades before mechanical pin setters came about.

Various trade exhibitions were held with American and foreign companies hocking their wares while presenting to exhibition goers the latest and greatest of contemporary living. The National Auto Show in 1900 was the first modern automobile show to feature the latest in automotive innovation. Back then, they were still mostly called horseless carriages and were viewed with as much skepticism as amazement. As part of the show, a track was laid down around the exhibition floor, along with a special ramp to allow auto makers to show off their contraptions’ hill-climbing abilities. There were also a number of braking and acceleration demonstrations and competitions, with about 31 vehicles on display. About 10,000 people attended the three-day show, each paying 50¢ to attend.

All sorts of major shows and events took place in White’s Garden — dog shows, circuses, operas, plays, demonstrations, rallies, exhibitions. As time went on, however, it became apparent that the Garden would not be able to sustain itself via its normal revenue streams. Just as things started to look bad for the Garden, along came Tex Rickard.

Of the many colorful characters who over the years had a passing affiliation with Madison Square Garden, few were more colorful than George Lewis “Tex” Rickard. Born in Kansas City, MO, Rickard was a former cowboy, marshal, gold prospector in Alaska, and saloon/hotel/gambling parlor owner, before moving to New York where he became famous as an early boxing promoter1. He was a man of his time, a combination Jack London frontiersman and a P.T. Barnum huckster. Like other swindlers, promoters, and showmen of his time, Rickard knew how to captivate an audience and how to build hype for his product. He was also a brilliant, spirited, and ruthless businessperson.

Tex Rickard was responsible for the building of two “Garden” venues, the founding of the New York Rangers NHL hockey team, and was a huge influence in the sport of boxing.

Rickard in 1920 bought the rights to promote Madison Square Garden. He used the venue to put on boxing matches, which brought in many paying customers. Although boxing was popular, “prize fights” were forbidden in New York, so to stay on the good side of the law, Rickard took advantage of certain loopholes in laws banning the sport and instead put on “exhibitions” where the boxers were not so much beating the shit out of each other as they were demonstrating fighting techniques. Over time and partly because of Rickard, politicians realized that there was a lot of money to be made with the sport, which meant more tax revenue, so they ended up relaxing the rules. It was these boxing matches that helped Madison Square Garden stay open for longer than maybe it should have.

Boxing would end up being the thing that Rickard would be the most known for in history, but he also got creative in his use of the Garden. In the summer, he would turn almost the entire main floor space into a gigantic swimming pool with slides and diving boards where aquatic and swimming exhibitions were put on. Not only that, but Rickard would open the pool during the summer months to customers willing to pay for a dip in the gigantic pool. Anything to bring in revenue.

Rickard is not the main focus of this piece, and there’s no way to do justice to a guy like him in this short section, but you can find out more about Rickard here, here, and here, and in this book and this book. He’s very much worth reading about.

One of the biggest events ever to take place in Madison Square Garden was the 1924 Democratic Party’s National Convention. This was one of the most contested and infamous conventions in U.S. history, complete with fist-fights, backroom dealings, and good old-fashioned racism. It was also the longest convention in U.S. political history, having gone on for 16 days and through 103 ballots before a candidate was chosen. Along with the usual political and regional divides that were commonplace at these conventions, there was a big rift between the two biggest and most powerful factions in the party, those being the New York Tammany Hall Democrats, whose views represented most of those in the northeast, and the white supremacist group, the Ku Klux Klan. Back then, the KKK was a major contingent within the party and during this particular convention, they were very active, very vocal, and very intimidating. It is for this reason that the convention became known among some newspapers as the “Klanbake”.

The 1924 Democratic Party’s National Convention was the last major event held at the Second Madison Square Garden. The convention was notable because of the tremendous amount of disunity and acrimony that came to light during the proceedings. It made today’s political conventions seem tame. (New York Public Library).

The fact that the KKK was a huge force in the party made Democrats in the Northeast, particularly those who were immigrants, Catholic, or Jewish, very uneasy. They wanted to do all they could to push the KKK from the party, and New York Governor Alfred Smith was the man they chose to oppose the radical racist elements of the party. For the most part, the KKK disliked Smith for several reasons. He was anti-KKK, was anti-prohibition, and was Catholic (the latter of which REALLY pissed them off). The candidate who the Klan did endorse was William McAdoo who was actually the leading candidate and the presumptive nominee going into the convention. McAdoo had previously served as Secretary of the Treasury in Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet, where he had much success in using his office to help finance U.S. involvement in WWI along with several other shrewd and deft economic moves. He was in many ways a progressive who had spoken in favor of workplace compensation, unemployment insurance, an 8-hour workday, and a minimum wage, all things you wouldn’t think your typical Klansman would be into, but they liked the fact that he was in favor of prohibition, a social conservative, and had seemingly no qualms with the KKK being a major party power. McAdoo had some baggage, however, that really didn’t sit well with others in the party. Aside from the fact that he didn’t reject the endorsement of the KKK, McAdoo’s reputation had been tarnished when it was revealed that he had taken money from an oil tycoon who had been implicated in the Teapot Dome scandal. The whole convention got super ugly on the tenth day when an estimated 20,000 robed and hooded Klansmen and their families gathered in New Jersey on the Hudson River across from New York and burned crosses and effigies of Smith, which could be seen from Manhattan.

Over the course of the convention, no fewer than 60 candidates at some point garnered at least one delegate vote, turning the entire proceedings into what seemed a disorganized, disgruntled, and disunited free-for-all. In the end, both Smith and McAdoo ended up cancelling each other out. Knowing that neither could win given the circumstances, both men stepped back from their respective candidacies. It was John W. Davis who ended up with the nomination after all the dust cleared, and went on to lose the general presidential election to Republican Calvin Coolidge.

An ugly political fiasco, the 1924 Democratic National Convention was the last major event to take place in the second Madison Square Garden.

One of the big problems with the second Madison Square Garden was that it was never really profitable. Sure it had iconic status, and they would pack the place at times, but the Garden itself had a high operating cost. Just lighting the Diana statue at night became expensive because of the amount of electricity needed to power the lights. At the same time, the city was expanding north, and as it moved north, the theaters that once lined 23rd street, all moved to Times Square, thus pulling away some of the foot traffic from which the Garden used to benefit.

The last group to hold the title to the Garden was the New York Life Insurance Company, which itself was looking for a new location to put its headquarters and no longer interested in holding onto the aging Garden. Seeing that the Madison Square area would be ideal for their new building, the New York Life Insurance Company had the Garden unceremoniously demolished in 1925.

Even though the Madison Square Garden building itself was heading toward its end the name still held a lot of value. Tex Rickard who still owned the rights to Madison Square Garden gathered funds from investors and built a new Madison Square Garden up on 8th Avenue and 49th Street, which first opened in 1925. Despite the fact that it was no longer on Madison Square, Rickard knew the name was too well-known to simply give up, so he shrewdly used it for his new, more contemporary, and cheaper-to-operate venue.

Ever the visionary/showman/business man/con man, Rickard didn’t stop at his new Madison Square Garden. He wanted a Madison Square Garden in every major city, in a way making Madison Square Garden less of a single place but more of a concept. Soon after he built the third Madison Square Garden, Rickard oversaw the construction of the “Boston Madison Square Garden”, whose name soon after it opened was shortened to The Boston Garden. That arena went on to become the home for some of the greatest basketball and hockey teams in history before it was closed in 1995 and demolished in 1998.

In the final analysis, it was Madison Square Garden’s own opulence that did it in. Expensive to operate, difficult to fill, and too extravagant to maintain, its passing was understandable and prudent, but is still somewhat of a disappointment for those in the present who would have loved to have wandered the Garden’s halls imagining them filled with crowds of Gilded Age New Yorkers shuffling about.

White’s Madison Square Garden will always be part of the conversation when discussing New York’s most beautiful buildings. It is also remembered as being one of the most culturally significant world venues at the turn of the 20th century. As for what stands today on the northeast corner of Madison Square on the block between E26th, E27th, Madison Avenue, and present-day Park Avenue South, there still lies the building that replaced White’s masterpiece, the magnificent New York Life Building, which in its own right is an architectural treasure.