Remember, 2 > 1. Always!

02/08/2017

Updated on 10/18/2022

German athlete Luz Long is quite possibly the ultimate Silver Medalist. He is the athlete who finished second to American Jesse Owens in the long jump competition at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but more than that, he made sports history with a gesture that stunned many who witnessed it. After their competition, Long, a white man, enthusiastically embraced Owens, a black American man, in front of an ecstatic crowd that included many high-ranking Nazi officials, at a time in Germany when such interaction between white and black people was frowned upon. Despite his gesture, Long wasn’t looking to make a political statement. The 23-year-old was the greatest long jumper Europe had ever produced and all he wanted was to compete against Owens, who held the world record for the long jump (8.13m), and who was largely considered the greatest athlete in the world. But what may be the most remarkable thing that happened during their competition was that Long himself may have actually helped Owens to win gold! That’s right, Long may have given Owens advice that allowed Owens beat him.

This is one of those feel-good stories that are usually too good to be true, and this case, much of what has been said about the encounter is not true. Some had been made up after the fact. Then again, some of the details are undeniable. But it’s a good story none-the-less with or without the embellishments and myth.

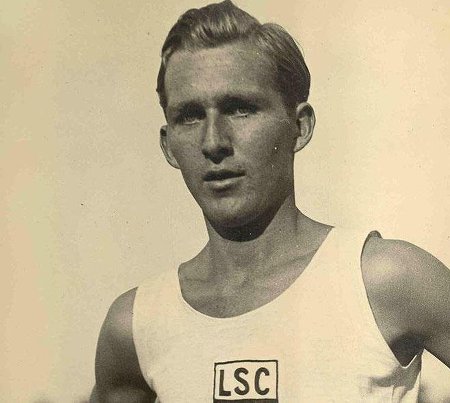

Carl Ludwig “Luz” Long was born in Leipzig, Germany, April 27, 1913, into a well-educated family that had a long history in the sciences. His mother, Johanna Hesse Long, was the daughter of a dentist, the granddaughter of the well-known 19th century surgeon Karl Thiersch, and the great-granddaughter of the famous chemist Justus von Liebig. In addition, Long’s father, Carl Hermann Long, was a well-respected local pharmacist. A sports enthusiast from an early age, Long in 1929 joined the Leipziger Sports Club (LSC) where he began honing his athletic and long jumping skills. A scholar as well as a world-class athlete, Long studied law at the University of Leipzig, where in 1939 he received a law degree with a concentration on sports management — a seemingly appropriate merging of passion and vocation.

Hitler looked forward to seeing his country’s athletes demolish the competition. According to Albert Speer, who would later become Hitler’s Wartime Armaments Minister, Hitler was “highly annoyed” by Owens’ accomplishments.

Germany during Long’s formative years became extreme in its politics and society when the Nazi Party came into power with a message of nationalism, Aryan supremacy, and intolerance. The Grand Poobah of Nazism, Adolf Hitler who became chancellor of Germany in 1933, turned Germany from a post-WWI wreck into a contemporary military state complete with propaganda, secret police, and good ol’ fashioned racism. One of the more insidious aspects of Nazism was that it came in under a guise of idealism, which was appealing to the youth of the period and led many to join its ranks.

Although it’s safe to assume that Long himself had reasoned opinions about the goings-on in his homeland, it’s hard in the present to determine for sure his political views. Records of his opinions on things non-sport largely do not exist and those accounts that can be found aren’t entirely reliable. Long for the most part was described by his family as being devoted to sport more than anything, but that could not have been the complete story. If nothing else, the fact that he studied law suggests that his thoughts weren’t limited to athletics.

At university, Long joined the National Socialist German Student League, which was a country-wide campus association that participated in rallies, demonstrations, and other political events. This was the same organization that went around Germany holding book-burning rallies, where they burned books written by Jews, communists, and most foreigners, as well as any books that ran counter to Nazism in even the most superficial ways. The main purpose of the Nazi Student Union was to indoctrinate and nurture the Nazis of tomorrow for the Fatherland.

It’s very likely that Long only joined the organization because it was simply what one did in 1930s Germany. He was studying to be a lawyer and joining such an organization would have been a good career move since he needed to be a Nazi anyway to hold a position in the legal field once he graduated. In order for Germans to have certain civil service jobs, being a member of the Nazi party was obligatory. Not in a nudge and a wink sort of a way, but as a flat-out requirement. Working professors, civil servants, and lawyers all had to all join up or get fired, and those seeking employment in those fields and others had to join up or not even be considered. When Long later served as a referendar at the court in Hamburg (in the German legal system, a referendar is a sort of intern/clerk trainee, or in simpler terms, a legal trainee) he was absolutely required to be a member in the Nazi party. But is that the full reason for Long’s participation? Perhaps Long believed in aspects of Hitler’s National Socialism to some degree and that he like many German people back then saw Nazism as an uplifting social and political force in Germany, which after WWI was a pretty crappy place to live for the most part. Did Long believe that Nazism would have brought about many beneficial societal reforms despite its extreme and diabolical “solutions”, or did he only join the party because he had to? Whatever his motive may have been for initially joining the Nazi Student Union, it’s almost impossible to determine or even understand his motives today, and we can never really know for sure how much of a Nazi he was. However, given his actions and demeanor, it’s a difficult argument to make that Long was in any way a hardcore Nazi. It is more than likely that the opposite was true.

Politics aside, Long was the perfect athlete for Germany to highlight at that time. Tall, strong, blonde, intelligent, and handsome, Long was amiable as well as athletic and represented all the strength and so-called “Aryan-ness” that Hitler so admired. At that particular Olympics, Hitler saw an opportunity to show the world the new Germany in what became known as the “Nazi Olympics”. He wanted everyone to see German athletes display their ethnic and racial “superiority” on the field of sport. In Long, Hitler saw the personification of his deranged theories and prejudices, a model for all other races, the perfect German.

Luz Long mid-jump during the competition.

The long jump competition in the 1936 Olympics took place on August 4, with 43 athletes from 27 nations competing in front of a crowd of about 110,000 excited and enthusiastic Germans. Also present were a great many rank-and-file Nazis, including Hitler himself.

The very obvious favorite to win was 22-year-old Jesse Owens. Sports prognosticators at the time generally felt that Owens’ toughest competition would come only from his fellow Americans and only in the running events. As for the long jump, seeing as how he had jumped decidedly farther than any human being in history, most thought Owens was a shoe-in to grab gold. Owens however felt differently. He was concerned about the long jumper from Germany.

Owens had never met Long before. He didn’t even know what he looked like, but he had definitely heard of him. Long was having a fantastic year. He had won several tournaments including a European Championship and had recently set a new European long jump record. Although that record was still about a foot less than Owens’ record jump, Owens knew that Long only getting better as a long jumper and was fully capable of beating him. All it took was for Owens to have a bad day.

Before the tournament began Owens stood next to his coach looking over the competition. Owens was never one to study up on other athletes, but at this event he was more curious about his competition than usual and wanted to get a look at Long. After a short while, a tall muscular athlete wearing gray training pants and black turtleneck came jogging out onto the field. It was indeed Luz Long, and on looks alone, he seemed a formidable force. Of his first impression, Owens later wrote:

“Long was one of those rare athletic happenings you come to recognize after years in competition — a perfectly proportioned body, every lithe but powerful cord a celebration of pulsing natural muscle, stunningly compressed and honed by tens of thousands of obvious hours of sweat and determination. He may have been my arch-enemy, but I had to stand there in awe and just stare at Luz Long for several seconds.“

This was different for Owens. He was never one to be in awe of particularly anything let alone another athlete. In his well-researched and well-written book Triumph: The Untold Story of Jesse Owens and Hitler’s Olympics, author Jeremy Schaap described Owens’ feelings:

“Long unnerved him, and he was suddenly and sickeningly reminded of the way he had felt a year earlier when he was running and jumping against, and losing to, Eulace Peacock. Long like Peacock, was conspicuously bereft of the fear Owens had grown accustomed to recognizing in the eyes of his competitors…And in an instant, he could actually feel all the confidence he had built up drain from his body.“

Luz Long and Jesse Owens at the Olympics. SM has so far been unable to confirm exactly when during the tournament this meeting took place, but it was titled (translated from German) “Tips for the Competitor.” To be perfectly honest, we’re not even sure that this photo is real. Long’s body seems a little oddly placed.

Long began the competition well, setting a new European record during his preliminary jumps and positioning himself nicely for the final rounds. Owens, on the other hand, didn’t look as good out of the gate. In fact in the qualifying round, he downright stunk.

The distance to qualify for the finals was only 7.15m, which Owens on a normal day could have made running backwards. But on that day, Owens was having a spell of bad luck. What he thought was a warm-up attempt was actually counted as his first jump. He hadn’t noticed that the officials had raised their flags to signal the start of the competition. Americans at the time had a tradition of running down the lane and through the pit as a sort of a good luck ritual, which is what Owens did. The judges didn’t know about this because athletes didn’t do that in Germany. Despite Owens’ and his team’s protest, the “jump” counted. This really disturbed the American.

On Owens’ second attempt, he was very much off his game. As he ran down the lane, Owens began pressing too hard and tightened up as he ran. This threw off his gate and caused him to jump with his foot over the foul line, thus negating the jump.

Down to his third and final qualifying jump, things weren’t looking at all good for the American. The very real possibility of an all-time epic choke was upon him, and with it, his place in history. It was during this dark moment that a friendly Luz Long went over to Owens and introduced himself in English. Owens was shocked. He hadn’t heard Long utter a word or show the least bit of emotion since the competition began, but there he was. Long could plainly see Owens’ difficulties and why he was having so much trouble making his qualifying jump. Astonishingly Long chose not to pounce on Owens but to help him remedy his issues. He suggested that Owens measure out a spot on the track about foot behind the foul line, and aim to plant his jump foot in between the mark and well before the foul line, thereby eliminating the threat of another foul. Long’s reasoning was that Owens could easily cover the distance necessary to qualify even if he jumped a few inches behind the line. By the rules of the sport, this was perfectly legal. In some accounts of the story, Long went so far as to place his sweatshirt near the mark so that Owens could see it better. Whatever the particulars Owens followed Long’s advice, which turned out to be good advice because Owens’ last qualifying jump was successful.

The chain of events here are a little off, but in the end you can clearly see Long come over, congratulate Owens, and put his arm around him. It did not sit well with the Nazi leaders.

The finals began that afternoon and Owens, having regained his composure, flat out ruled from the get-go. He was ahead of the pack after his first jump in the first round. Then with his second jump, Owens posted a 7.87m mark which was to keep him in the lead for the rest of the round and into the second. Long for his part, kept pace — his third jump was only 3cm shy of Owens’ mark.

The crowd had been good throughout the competition, and grew louder as the competition went on. Many were cheering Owens on while many others were hoping to see their homegrown European Champion pull ahead. The first jumps of the second round came and went. Each athlete had two more tries to post the best jump.

Long could feel the moment and like any great competitor he saved his best for for when he needed it most. He started down the track as he always had, gaining speed and momentum, and just as he reached the take-off board, Long took off over the pit. It was a brilliant jump. When the dust cleared, the measurement read out was 7.87m, tying Owens. The crowd nearly exploded with excitement. It was a fantastic moment for the talented young German, but it was short-lived.

On his second jump of the round, Owens soared to a 7.94m mark, well ahead of all the competition. The crowd, except for all the racist Nazi leaders present, cheered wildly. Owens may not have been their hometown guy, but he was still a celebrity.

They were now down to their final jumps, Long had one more chance to overtake Owens, but it was not to be. On his last jump Long fouled, thus surrendering the gold to Owens. For his part Long would be awarded the silver medal and would later go on to grace the pages of SilverMedals.net 81 years later.

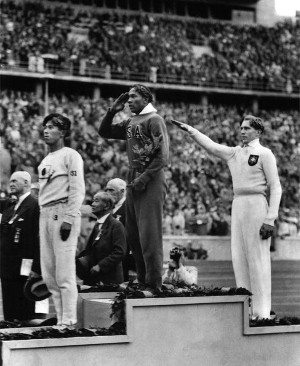

Left to right: Naoto Tajima* of Japan (bronze), Jesse Owens (gold) of the U.S., and Luz Long (silver) of Germany. I’m quite sure, my fair reader, that the irony of this moment is not lost on you.

The match was already decided but Owens still had one jump left. He could have chosen to not take it, which is what athletes would usually do, but Owens was a true competitor to the point that if there weren’t anybody else with whom he could compete, he’d compete with himself. As disappointed as he was, Long was as good a sportsman as he was an athlete, and he wanted to get a good look at Owens’ last try. So he took a position near the end of the landing pit to get the best view of his rival’s jump. Owens stepped up, got in his ready position, and then sped down the track toward the pit. Gathering all his momentum, Owens soared out over the pit. As he came down, everybody in attendance could see that it was a fantastic jump. It ended up being measured at 8.06m, a new Olympic record! That alone would have been a brilliant conclusion, but just as Owens got up from the dirt, an enthusiastic Long who couldn’t contain his excitement immediately ran over. He and put his arm around Owens and shook his hand, and the two men walked away from the jump pit, arm in arm, smiling.

It was a very warm and inspiring act on the part of Long in the way he embraced the man who beat him so soundly. Throw in the fact that Long was a white man in Nazi Germany embracing a black American in front of a disapproving and very racist Hitler, it was a display that the world had not seen before or since. Needless to say, the moment didn’t exactly sit well with the Nazis in attendance.

Even when he saw with his own eyes how a black man could beat out his best athletes, Hitler, a master of distorting science and twisting social history to justify his own racist and narrow views on people, was able to dismiss Owens’ victories outright. According to Albert Speer, who was one of Hitler’s most trusted ministers and very influential within Germany, Hitler said that Owens victories were really more of an embarrassment for the Americans for needing their “black auxiliaries” to beat the Germans. From his memoir Inside The Third Reich, Speer wrote:

“People whose antecedents came from the jungle were primitive, Hitler said with a shrug; their physiques were stronger than those of civilized whites and hence should be excluded from future Games.“

Deputy Führer and Nazi goon Rudolf Hess. He was a fanatic who during WWII flew a plane to Scotland to negotiate an end to the war. This was done without Hitler’s permission and without prior Allied knowledge. Hess hoped to convince the British to end the war and let Germany have the continent. Ignored by the British, forsaken by the Nazis, Hess very much fit the clinical definition of “batshit crazy”.

Long’s gesture toward Owens definitely did not go overlooked by the Nazi brass. According to his family, Long received a very nasty talking-to from one of Hitler’s enforcers, the Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess, for having embraced Owens the way he did in front of the crowd. Hess was a longtime underling of Hitler to whom he was fanatically devoted and was not one to let any slights against the Reich go unchecked. So when he saw Long after the event, along with some likely threats and warnings, he told Long to “never embrace a negro again”.

Owens later claimed that the two men became good friends after the event and corresponded until WWII broke out. In this 1966 documentary about his experiences at the Berlin Olympics (filmed in 1964), Owens can be seen telling his story to Long’s son Kai.

After winning a silver medal in the long jump, Long went on to finish 10th in the triple jump at that same Olympics. He continued with his athletic career afterwards and went on to win several more European tournaments further solidifying his place as one of Germany’s finest athletes, while also continuing to pursue his career in law. Unfortunately, Hitler decided to invade Poland in 1939 and start WWII. Two years later in 1941, Long was drafted into the army, where he served as a sports coach and physical training officer until he was transferred to a flak regiment and sent to Sicily. It was there he was wounded during an attack by U.S. soldiers, captured, and brought to a British military hospital near Acate. Long died there on July 13-14, 1943, at age 30. He never saw Jesse Owens again after the 1936 Olympics.

The story of Owens and Long always seemed a little too “fairy tale” to most sports historians and there is quite a bit of skepticism about Owens’ own account. The events have been put to film several times, the most notable being Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia documentary (Part 1, Part 2). Each depiction gives a slightly different account of the events, which clouds the history somewhat more. What really didn’t help was that Owens himself told different versions with some obvious key fact changes and embellishments. But the main questions that give historians fits are:

According to this article on NPR.org, in 1965 Tom Ecker, author of Olympic Facts and Fables, straight up asked Owens if the story was true that Long helped him and that they became friends. Ecker said that Owens somewhat admitted that he hadn’t met Long until after the event, but that wasn’t what he told people at speaking events. Owens allegedly told Ecker that he preferred to tell the idealized version of the encounter mostly because his audiences liked it. Owens’ children were not able to shed any more light on the subject because they had never really asked him and only knew of the story from other sources. Also according to the article, the famous sportswriter Grantland Rice said that he was watching Owens the entire time at the Olympics and didn’t see him once talk to Long.

Long and Owens having a conversation while posing for photos shortly after their competition. From the looks of their friendly interaction, Long doesn’t seem to be acting very Nazi-ish at all.

No offense to Rice, but this cannot be accurate at all. The two athletes had to have spoken at least once during the event at some point — the photo above shows the two men talking during the event. But say the photo was somehow doctored and not what it purports to be, or say that it was taken after the event, if you watch the way Long embraces Owens after his record breaking jump, it’s quite evident that there must have been some sort of relationship or even small talk beforehand. If anything, they look like two teammates embracing after a good meet. Whether or not Long actually helped Owens, that much has been told so many times that some discrepancies can be chalked up to either embellishment or the normal erosion of events in one’s memory. Sure it’s very possible that Owens himself came up with the idea of jumping several inches before the foul line and only attributed it to Long later. But then why would Owens make it up? And why would he stick to it until his death in 1980?

Long’s son Kai, in an interview here, shed a different light on his father helping Owens and later embracing him. It somewhat dispels the the spirit of the myth, but also causes the actual act of Long helping Owens seem less far-fetched. He suggests that such actions were common in amateur athletics back then, and that even though athletes were competing against each other, it was not uncommon for them to offer each other advice. Today, such help would seem almost inconceivable in the dog-eat-dog world of international competition, but back then, amateur athletics was indeed amateur athletics. Those athletes were sportsmen, enthusiasts, and competitors. Not enemies.

As for whether or not there was any political motive, Kai insisted that there was no motive behind the act of embracing Owens and that his father was simply congratulating the Olympic record holder. Indeed from the looks of the tape, Long running over to Owens seemed entirely impromptu. But even if it was just a quick burst of emotion in Long running over to Owens, Long wasn’t stupid; he had to have known that this embrace of Owens would have been a problem in Nazi Germany. The part where he received the strong rebuke from Hess for embracing Owens was very true.

As for their relationship after the Olympics, Long’s family saw no evidence for there being a correspondence, but admittedly they couldn’t entirely rule out the possibility of there being one either. It’s more likely as was described in Schaap’s book, that the two men went back to the Olympic village area, had a good long visit, and then went their separate ways. Whether or not they remained friends and corresponded afterwards is difficult to verify. It comes down to whether or not you think Owens was embellishing, which he more than likely was.

The whole deathbed request portion of the story is just pure Hollywood bullshit. It never happened.

Owens’ victories, at the 1936 Berlin Olympics and Long’s part in that story is one that coaches, teachers, sportscasters, and pop historians would trot out as a tale of the overcoming of racial divides, the power of sports, and the power of good sportsmanship. Whatever the inconsistencies, the verifiable facts of the story need no further embellishment to be meaningful and notable. Indeed Owens’ performance at the Games was a bitter bit of schnitzel for the Nazis to swallow because he, a black American, ended up beating the “superior” white athletes of Germany to win four gold medals in the 100m, 200m, 4×100 relay, and the long jump. The situation was made awkward when the German athlete Long did something that no dyed-in-the-wool Nazi would ever do. He ran up to Owens after the American’s record-breaking jump, shook Owens’ hand gleefully and put his arm on Owens’ shoulder like they were old pals. The two athletes than walked off together right in front of the box where a stewing Hitler was sitting and looking on. It was one of the finest examples of good sportsmanship the Olympics has ever seen. And for his part in it, Luz Long will always be remembered as one of the greatest sportsmen the world has ever known.

(Note: On October 18, 2022, Luz Long’s family auctioned off the 1936 silver medal he won in the long jump for just under $488,000. You can read about it here.)