Where second is always first!

11/14/2017

Updated on 09/06/2022

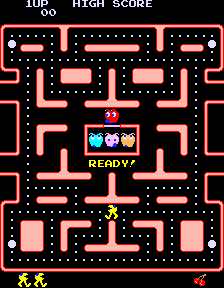

When Pac-Man came out in 1980, it was big. I mean really big. Like “stand in a 10-person line to play for just a few minutes” big. For the price of 25¢, you could guide Pac-Man — a little, binge-eating, yellow, three-quarter circle — through a maze loaded with tasty little white pellets while being chased by four colorful little ghosts named Inky, Blinky, Pinky, and Clyde. It was a huge success for Namco, the company that made Pac-Man, and for video gaming in general.

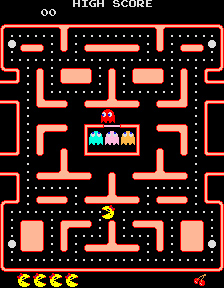

Ms. Pac-Man the sequel to Pac-Man and the second game in the Pac-Man series was an even bigger success. The game itself was the same, but the game play was just better. Both Ms. Pac-Man and the ghosts were faster. There were 4 mazes as opposed to the one that you kept playing over and over again in Pac-Man. The ghosts were “smarter”, that is, they weren’t as predictable as those in Pac-Man. And of course there was Ms. Pac-Man herself, who was just so darn cute.

Ms. Pac-Man outdid her predecessor in almost every way. It was a better game. It sold more game units. It made more money on those units. It was the perfect follow-up to the worldwide craze that was Pac-Man — a phenomenon on top of a phenomenon. But oddly enough, it wasn’t even originally meant to be a sequel. In fact, Ms. Pac-Man started out as a man.

Ms. Pac-Man game cabinet.

Ms. Pac-Man started out not as a standalone game, but rather as an “enhancement” to Pac-Man. A sort of hacked version that tacked onto old Pac-Man code. It wasn’t even developed by Namco, but by a bunch of college kids led by two MIT students named Doug Macrae and Kevin Curran. The two had a small business running what was called a video game “route” around MIT. What that meant was they would supply, service, and operate the arcade cabinets around campus and later for other businesses off campus. Having originally started off with a donated pinball machine and three Missile Command cabinets, they were making pretty decent money until the inevitable happened — people started getting bored with the old games and stopped playing as much, which meant fewer quarters for this dynamic MIT duo. This compelled Macrae and Curran to get into a new sort of business, one that could extend the lives of their and their potential clients’ machines. After forming the General Computer Corporation, they began building what they called arcade unit “modification kits”, or hacks that they sold to businesses who wanted to upgrade their old arcade games.

The way the whole arcade video game economy worked was that arcades, pizza shops, or owners of other video-game appropriate venues would buy the big cabinet with the game, put it out there for people to play, and then collect the quarters that flowed in. This was all fine and dandy when the games first came out, but after a while, there was always a drop-off in revenue. For one thing, as players got better, they spent a longer time playing, which mean that their single quarter could go a longer way. Then there was game interest, which would naturally wane over time. So it became important for people looking to make money off video games to buy new games, but this was expensive. It would have been better if they could find some way to extend the life of those old games — possibly by adding some new wrinkles to the old games — to make them seem more fresh and new thereby increasing the return on their initial investment.

This is what Macrae and Curran and the rest of General Computer were thinking when they came up with their idea to not build their own games in game cabinets, but to build “enhancement” kits that could be made easily and very cheaply, and installed in old games. These kits included some cheap electronic boards and some piggyback code that would not change the fundamental code of the old games, but would instead be built on top of their underlying structure. Doing this, General Computer could change some of the screen colors, change the look of the villains, add some new logic to make the game flow differently. To achieve this, they would put together circuit boards programmed with the their new and enhanced logic specific to the game they were modifying, then plug the boards into the old game cabinets. They first did this for their Missile Command units, which resulted in the new game called Super Missile Attack. The enhancements weren’t huge — mostly a few color changes and more missiles and bad guys to shoot at — but it gave gamers reason to start using the cabinets again, thereby extending the life of the old system. It was a pretty smart move because not only did they see their old Missile Command units become profitable again, other arcade route owners were also interested. Having achieved a degree of financial success with their Missile Command enhancement units, General Computer set it sights on the king of video-game kings Pac-Man.

Pac-Man was not only a successful video game, but a cultural phenomenon that spawned toys, TV shows, and pop songs. As a game however, it got old fast. It was the same maze over and over again with no change except that the game sped up the further along you went. There were also many gamers who had figured out the game logic enough to be able to achieve very high levels on one quarter, which of course ate into profits and that was a bad thing. Oddly enough, when General Computer created their Pac-Man modification kit and called their new mod Crazy Otto.

This is flat-out weird. Here in all its glory is Crazy Otto before it got turned into Ms. Pac-Man.

The game was basically the same — a weird little yellow thing running around a maze eating pellets while being chased. Except in this modification, that weird little guy had legs and big blue eyes, which is sort of unsettling when you see it, and the things chasing him weren’t ghosts, but were more like little monsters with blue feet. They were the same colors and had the same eyes as the Pac-Man ghosts, so you could see pretty easily the derivation, which also hints that the mod kits added a bit of extra processing power to the game circuitry. Along with these minor yet significant visual differences there were also several game-play improvements over the original.

For one thing, it wasn’t just one maze you went through. There were four, which doesn’t seem like a big deal today, but it was three more than Pac-Man had. The mazes got more interesting also. There were longer straightaway sections with fewer escapes causing the player to think more strategically. In all but one of the mazes, there were two sets of portals to go from one side of the screen to another; the lone standout only had one set.

The ghosts and Crazy Otto himself also moved faster, which made the game both more fun and more difficult. But probably the biggest change to the ghosts was that there was more randomness put into their movements so that they were more difficult to predict and made gameplay more challenging in a fun way. (See box below.)

Other small enhancements were made such as the fruit snacks Pac-Man could eat. Instead of being stationary, they would bounce around the maze and Crazy Otto would have to catch them while still dodging monsters. Altogether it was a pretty darn good upgrade.

Ms. Pac-Man marketing art from Midway Games.

Around the time General Computer was building Crazy Otto, they were being sued by Atari, the maker of Missile Command. Atari was not happy with General Computer’s enhancement kits as they believed the small upstart was cutting into their profits and worse yet, messing with their game code. General Computer asserted that their kits in no way changed the fundamental software and hardware architecture but were add-on supplements that enhanced the old game — sort of like switching out the boring stock tires on a new car for high-performance racing slicks. Without getting into the legal stuff too much, Atari could see that it was going to be a difficult case to win. So they made a deal with General Computer. Atari would pay General Computer $50,000 per month to make games for Atari. In return, General Computer agreed to stop making their enhancement kits. Not a bad deal, since making games is what the founders of General Computers really wanted to do. But General Computer didn’t want to let Crazy Otto just fade off into obscurity, especially when there was such a lucrative market for their kit. Having already converted a few Pac-Man games, General Computer approached Midway Games, the American game cabinet distributor for Namco and offered to sell Midway their Crazy Otto enhancement. Midway, unbeknownst to the General Computer guys was somewhat desperate to find something to follow up Pac-Man and had just recently stopped production on Pac-Man cabinets. So Midway convinced General Computer to not make Crazy Otto an enhancement kit but to make it into a full-on sequel to Pac-Man.

Here’s the final Ms. Pac-man product.

Pac-Man was the first major arcade game that attracted women. Before Pac-Man, arcades were big Y-chrome sausage-fests filled with young dudes playing games that mostly involved shooting stuff. Pac-Man was different. There was no shooting or killing, just a hungry yellow disc eating pellets. So when it came time to make a sequel, in what could be seen as blatant bit of sexual stereotyping on the part of Midway or as an explicit marketing plan to get more women into arcades, it seemed only natural to the company bosses that the new Pac-Man should be a woman. But what to call her? Pac-Woman? Pac-Girl? Miss Pac-Man? Mrs. Pac-Man? The decision to go with Ms. Pac-Man largely played out over a 72-hour period before production on the new game was to begin. In the interscenes between certain levels of the new game, the creators told a story of the courtship between Pac-Man and this female Pac-Man. In the last scene, together they make a Baby Pac-Man. Right there, that ruled out any Pac-Girl, or Miss Pac-Man, the latter because the creators didn’t want conservative groups getting hung up on Baby Pac-Man’s sinful conception. The creators didn’t want Mrs. Pac-Man because that would imply she was already married and therefore there’d be no courtship. In the end, they decided on the more feminist sounding Ms. Pac-Man to please everyone. To further this point the designers put a bow in her hair, a mole on her cheek, gave her big red lipsticky lips, and long eyelashes to make her look as stereotypically feminine as they could. Crazy Otto was no more.

Here’s a closer look at the banner art on the Ms. Pac-Man cabinet. Aside from the fact that the game’s heroine looks a bit overly sexified here, the eager and lustful gaze of the obviously male ghost is just plain unsettling.

When Ms. Pac-Man hit the arcades in 1981, it was an instant hit. Pac-Man fans loved the new game play, and even more women and girls were attracted to it than the previous game. Money was rolling in for arcade owners, one quarter at a time, and after all was said and done, 150,000 units of Ms. Pac-Man had been sold, outselling the original Pac-Man by at least 50,000. It was a runaway success. It even translated well to the home console, unlike Pac-man, whose creators must have either had some serious contempt for home gamers or simply had their heads rammed many miles up their collective butts.

Anyone who ever played Pac-Man on Atari 2600, the only home console it was available on, knows that it was a complete and absolute shit show. It looked almost NOTHING like the arcade version. The colors were an ugly blue and orange, the ghosts flickered. Pac-Man himself was barely circular, he never looked up or down when going in those directions. The ghosts were all one color and hard to see, and the sounds were simple and computery, even for then. It was possibly one of the most cynical and poorly executed releases in the history of home video gaming. Despite all this, Pac-Man ended up being the biggest-selling game ever for the Atari 2600 with over 7 million units sold.

Ms. Pac-Man on the other hand, although not as crisp as the arcade version, was a far better port. For one thing, the ghosts were different colors. You could identify each one, which helped in knowing their “personalities.” The sounds were mostly the same as the arcade version, and Ms. Pac-Man looked very much like she did in the arcade complete with the lipstick and hair bow. You could actually convince yourself that the arcade version wasn’t necessary. Of course no games then looked or played better than they did on the big cabinets. Ms. Pac-Man went over quite well and is widely considered one of the best of the Atari 2600 games.