Where second graders beat up on first graders!

05/29/2018

Updated on 09/24/2022

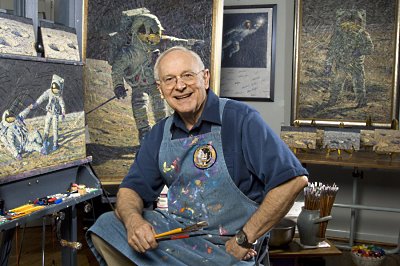

When Alan Bean retired from NASA and decided to become a full-time professional fine-art artist, he had to shed his aeronautical engineering and astronaut self to allow his inner artistic vision come through to the canvas. Not an easy task for the former Apollo 12 astronaut, one of only 12 men to have walked on the surface of the moon, a person who spent his entire adult life in the very un-artistic no-BS world of naval aviation and astronaut training, where attention to detail and doing things “by the book” was essential. His initial forays into painting were indeed by-the-book, he was an accomplished amateur who borrowed styles and copied techniques in much the same way that other amateurs do, but for a man who once walked on the surface of the moon and who was always looking for the next challenge, being an amateur wasn’t enough. He had a vision that he wanted to share but it wasn’t the vision he was producing. In trying to become a fine-artist Bean found that his trained astronaut’s analytical mind was a hindrance in trying to tap into his inner thoughts on his experiences. To fully express his inner visions of the moon, space travel, and the camaraderie of the astronaut corps, Bean had to shed his old self.

“I wanted to paint the Moon in a variety of beautiful colors in the same way Monet painted the gray granite Rouen Cathedral and the yellow-brown grainstacks,” Bean once wrote, “…to be true to myself and what my eyes had seen, I had to replace my Astronaut, Engineer and Scientist Heart with the Heart of an Artist. That was not easy but it sure feels right today.”

Bean first took up painting as a hobby in 1962 after taking a water-coloring class. It remained a hobby until he retired from NASA in 1981, and began his “second” career as an artist painting images of the lunar surface and other astronaut-themed scenes using bright and dazzling colors, though still faithful to the overall shapes and shades he saw while standing on the moon back in 1969. His subject matter like the lunar module and astronaut suits were spot on the way he depicted them, but he also had a highly Impressionistic style which helped Bean present the sheer awesomeness and loneliness of space. He often employed spacecraft models and what were essentially toy astronauts to first create the scene which he would then paint. His attention to detail always acute, Bean used a very bright and focused lamp to simulate the sun as it swept over his scenes.

Alan Bean on the moon in 1969 holding a sample container filled with lunar dust. Astronaut Pete Conrad took the photo. You can see him reflected in Bean’s helmet visor. (Image by NASA)

Bean preferred using acrylic paints on aircraft plywood, but he would also mix into his paintings tiny pieces of the artifacts he collected over his time as an astronaut — his mission patch, bits of lunar dust from his clothing, tiny pieces of foil from the lunar module’s heat shield. He very much put pieces of space into each of his paintings. To capture what he felt was the texture of the moon, Bean would layer his paintings with thick coatings of resin and paint, and he would then and use a hammer — the very hammer he used on the lunar surface to collect rock samples — to create texture and a bit of relief. In some paintings, you can see footprints in the relief of the paint, which Bean created by using a lunar space suit footpad similar to the one he wore on his lunar ride.

Reviews of Bean’s work have largely been muted at best, but there was also a general acknowledgement of his unique vision. The New York Times art critic Roberta Smith in this 2009 review seems to capture what many may think of Bean’s work quite well. For the most part, she said his paintings seem too similar to each other and a bit formulaic, which is true. On the other hand, and as Bean himself claimed, he wanted to depict a subject that he cared about deeply, which was his journeys through space and the people with whom he made the journey both up in the spacecraft with him, and down on the ground supporting him. Of course, being the only true moonwalker to delve into the artistic world, he gets a little more leeway in terms of the general art world. It’s clear when you read about him and listen to interviews that he wasn’t just some old retired guy looking to cash in on his fame by making moon paintings. He painted what touched him the deepest, and when a guy who walked on another world chooses to share what touches him deeply, the rest of us had better pay attention.

Alan LaVern Bean was born March 15, 1932 in Wheeler, TX. As a young boy, Bean wanted nothing more than to be a pilot — people who he saw as heroes. After graduating from the University of Texas Austin in 1955 with a degree in aeronautical engineering, Bean entered the Navy where he became a fighter pilot, then later a test pilot where he would evaluate other aircraft. In 1963, Bean was selected by NASA to join the 3rd astronaut candidate group, most of whom flew in the Apollo project. Bean himself was chosen to be one of three astronauts (along with Charles “Pete” Conrad and Richard F. Gordon) to make the second landing on the moon as part of the Apollo 12 mission, which took place on November 19, 1969.

Bean was front and center of one of the more dramatic moments in the Apollo 12 story, when soon after liftoff, lightning struck the Saturn V rocket they were riding not only once, but twice, completely messing up the onboard instruments. The guys on the ground in the control room were seeing all sorts of errors popping up on their screens, while the three astronauts in the space craft were seeing their entire instrument panel light up with warnings and errors. The extraordinary amount of time spent by both the ground crew and astronauts over endless hours of training and simulation paid off in that moment. One of the managers on the ground at mission control, a guy named John Aaron, remembered a similar incident that occurred during an earlier simulation, where the instrument panels went haywire, emphatically suggested that the crew in the spacecraft “set ‘SCE’ switch to ‘Aux’”. Almost everyone at mission control along with two of the astronauts in the Apollo spacecraft were dumbfounded. Most of them didn’t recall the setting or even know off-hand where the actual switch was. Luckily for everyone involved, Alan Bean remembered the setting and made flipped the switch to aux, returning normal power to the instrument array, thus saving the mission. (The whole incident was dramatized in the fantastic HBO series From the Earth to the Moon.)

Alan Bean’s artwork on the cover of the July 2006 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction. (www.asimovs.com)

Bean and Conrad made their lunar landing on November 19, 1969, and spent the next day conducting research on the lunar surface. They collected lunar rock and dust samples, set up various experiments, took numerous photos, and even collected pieces of the U.S. space probe Surveyor 3, which was located several hundred feet from their landing site, to bring home for analysis. In all, it was a very successful mission.

For his second and last trip to space, Bean was the spacecraft commander for second mission to the bygone U.S. space station Skylab. During that mission, Bean along with his crewmates Owen Garriot and Jack Lousma set the then-record for the longest single period spent in space (about 59 days).

Bean’s passing on May 26, 2018, at the age of 83 was a sad day for space enthusiasts and for those who appreciated Bean’s contributions to the arts. Aside from losing a seemingly nice guy who made one of the greatest journeys in human history, the world lost a remarkable person who was able to communicate with an artist’s eye the sights and visions of a place that only 11 others in history had since seen. Measurements, experiments, the taking of soil samples, all those things could be performed by robotic probes operated from Earth at a fraction of the cost of sending people to do the same job, but robots cannot convey the feeling of standing on another world, looking at the Earth rising and setting in the sky, and the excitement and fear that goes with being an explorer in space. Bean showed that space exploration could reward humanity not only with scientific achievement, it could also provide new artistic perspectives on life, the universe, and everything, unfathomable to those of us who’ve never left Earth or walked on another celestial body.

“Artists are nice things to have around,” Bean once said. “It just further celebrates one of the great human accomplishments.”

Please have a look at the images below of Alan Bean and his work. You can read his full obituaries here, here, and here. And you can see a nice video tribute produced by NASA here. You can also view a fuller catalogue of Bean’s paintings here.