Where the second biggest is still pretty darn big!

10/24/2017

Updated on 09/10/2022

Sputnik 1 was successfully launched by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, becoming the first artificial object to reach Earth orbit. Having been launched during the Cold War era, this tiny, beeping, ball-shaped satellite caused great concern among many paranoid red-scared Americans for whom the event was not so much a great moment of scientific achievement, but rather a disconcerting development in the Soviet-American balance of power, which put the Soviets thoroughly ahead of the U.S. in the so-called “space race”. Pleased by their new-found prominence, Soviet leadership demanded that their next launch have even more “wow” factor built in.

Sputnik 2, the second artificial satellite to orbit the Earth, was a very different craft from Sputnik 1 and had a very different mission. Aside from the usual upper atmosphere readings and telemetry data that Sputnik 2 would send back, the mission would also put the first animal into orbit around the Earth. The animal chosen for this historic mission was a cute little doggie named, Laika.

There had been several rocket launches into the upper atmosphere throughout the late 1940s and 1950s, many of which carried animal passengers into the upper atmosphere but none of them reached orbit. Fruit flies, mice, dogs, and monkeys of all flavors were among the animals blasted into space by both the United States and Soviet Union over those years. The goals for those animal flights, aside from testing rocket and capsule function, was to prove that living organisms could withstand the shock of launch and the ordeal of actually being in the upper atmosphere and space.

Veering off on a slight tangent to this post…

the first animals to actually reach space were a bunch of fruit flies that were launched by the U.S. in 1947 aboard a captured German V-2 rocket. The purpose of that flight was to see if any living organism could survive the flight and radiation exposure involved in space travel.

Albert II was a rhesus monkey and the second animal to be shot into space. Although Albert II survived launch and his time in space, his parachute failed to deploy he died on impact. (Photo by NASA).

The second animal to reach space was a rhesus monkey named Albert II. He was blasted into space on June 4, 1949, atop an American modified V-2 rocket, and was supposed to return to Earth unharmed. Unfortunately, his craft’s parachute failed to deploy and the little monkey died on impact.

(You may be wondering why it was Albert II who was the second animal into space and not Albert I. Sadly, due to one of many malfunctions that plagued early space exploration, Albert I suffocated while riding in his craft, possibly before his spacecraft even left the ground. Poor monkey.)

Having an animal go up on Sputnik 2 put the Soviet scientists in a bit of a bind. There was no way in hell they would be able to construct a reliable life-support system for Sputnik, not to mention a re-entry system, in such a short amount of time, but Soviet leaders were intent on showing up those no-good, capitalist Americans. So as is almost always the case in situations where the science runs counter to what politicians and military leaders want, they dismissed the scientists’ reservations and insisted on sending a dog into space no matter what. What with those ridiculous mission parameters and short timeline, bringing the dog back from orbit was simply not going to happen.

Not much was known about little Laika before she became a canine cosmonaut. She was a small, 2-year-old, stray, part-Samoyed terrier mutt, who was caught as part of a big roundup of stray dogs around Moscow for use as potential spacefarers. Interestingly enough, scientists working with animals destined for space travel were specifically looking for strays to be used in space as opposed to dogs raised in captivity. Using a line of thinking that was uniquely Soviet, their scientists believed that stray dogs were better suited for space travel because they were used to living under tough conditions. The Soviets didn’t want any of those well-treated bourgeois dogs as they were deemed were too soft for space travel.

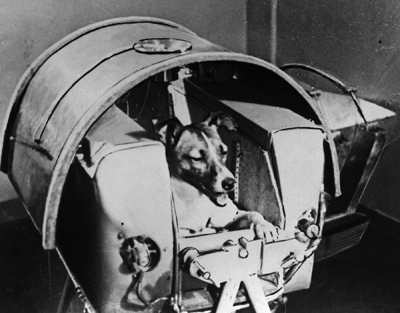

Laika, pictured here strapped into her harness was an unfortunate casualty of early space exploration. Whether or not it was necessary for her to be shot into space is still the subject of debate today. (Pubic domain).

Female dogs were preferred over male dogs partly because they tend to be calmer and easier to handle. From an engineering standpoint, they were smaller and could fit easily into the tight spaces, which any cabin on any craft was sure to have. Possibly the biggest benefit of female dogs at that time was that the little poo and pee collection systems they devised for the craft worked better with girl-dog parts than it did with boy-dog parts.

When all was taken into account, as well as training, behavior, and overall demeanor, Laika stood out as the best choice for the mission. When the launch day came, Laika was fitted into her harness and hooked up just as she had done during her training, however, the launch had to be delayed.

The craft carrying Laika had been built quickly (just under 30 days) and because of that there were a number of last-minute technical problems that cropped up. The craft ended up being delayed three days on the launch pad before lifting off. During those three days, Laika was strapped into her capsule with two of her handlers near her the whole time to keep her company. Finally on November 3, 1957, Sputnik 2 with Laika the space dog on board lifted off.

At first, things seemed to go according to plan. The rocket lifted off and reached space as it was supposed to. Sputnik 2’s protective shield, or faring, which is used to protect the craft during launch, jettisoned as planned, but then things started to go wrong pretty quickly.

If you were to read the press releases the Soviet government issued at the time, they would have said that Laika showed some signs of stress on launch, but that she calmed down and ended up having had a good flight, before being peacefully and painlessly euthanized in space about a week after launch, as per design. That turned out to be a complete lie, according to Dimitri Malashenkov, a scientist who worked on the Sputnik 2 project. Laika’s death was fear-filled and agonizing.

Malashenkov shared information about Laika’s flight at a space conference in 2002, and put to rest many lies and misconceptions about Laika’s flight. During training, Malashenkov claimed that the dogs were treated very well even as they were subjected to many of the same tests that future cosmonauts would have to endure. They were subjected to trips in the centrifuge, strapped into harnesses, and were trained to deal with the confinements of the capsule, which meant keeping the dogs in increasingly smaller cages over a period of 15 to 20 days. But they were always cared for during and after their tests to help reduce the stress they were feeling. Several scientists even grew close to the dogs.

From the minute Sputnik 2 lifted off from the launch pad, poor Laika, chained in place to prevent her from tumbling about the cabin, had been freaking out. Her pulse rate shot up indicating that she was extremely stressed and terrified, and you can’t blame her. She really had no idea what was happening except that she was tied up in a tight metal rumbling box.

Once she reached weightlessness, she started to calm down, but it took a long while for her heart rate to decrease. It was pretty obvious that she continued to be scared out of her doggie mind and was indeed suffering greatly. Data from the capsule showed that soon after the start of the mission, heat and humidity inside the capsule increased greatly to about 104 °F (40°C), which especially for a dog is fatal. For several hours of her flight, data showed that she was indeed eating her food, but that she was still stressed. As Malashenkov said, on the ground, the dogs would calm down quickly because the handlers were there to help, but in space, Laika was all alone, which for a social animal is not a good place to be even under good conditions. Of course, they never simulated the high temperatures and humidity in the capsule that Laika was experiencing in her little metal craft.

As the mission went on, Laika’s heart rate fell drastically and her pulse began to fade. For a while, all the scientists could detect was a faint heartbeat. Finally, after about 5 hours and 4 orbits, Soviet scientists couldn’t detect any further signs of life. It was determined that Laika died from overheating and stress — a very agonizing way for the charismatic little stray to die.

Laika’s body orbited the Earth more than 2,500 times before she and her craft burned up on re-entry in April 1958.

This monument to Laika was installed in 2008 in Moscow. She also appears on several other monuments dedicated to Soviet pioneers of space. (Public Domain)

It wasn’t until after Sputnik 2 was launched that the Soviet government told the world that they never had any intention of bringing Laika back. This drew widespread criticism from around the world and even within the Soviet Union where such dissent was a no-no. The Soviet government did what they could to pacify critics by depicting a noble and humane death for the space dog. Even so, it sparked an ongoing debate about the ethics of using animals for testing spacecraft especially when those tests would most assuredly lead to the animal’s death. Since then, several of the Soviet scientists involved in Sputnik 2 have admitted that there was not enough science gained from the mission to justify Laika’s inhumane treatment and tragic death.

Today Laika is remembered as a heroic symbol of all the animals that were used in experiments in early spaceflight, and she continues to be an inspiration for art, music, and literature. Her story also serves as a collective conscience check for all our scientific ambitions. If we’re to willingly send a dog or any animal into any situation where we know they won’t come out alive, we’d better have a damn good reason for doing so.