Where the second to call it gets shotgun!

12/19/2016

Updated on 10/20/2022

Thomas William Burgess got up on the morning of September 5, 1911, ready to make history. Having already tried and failed 15 times before, he knew what he was up against. He wanted to become the second person to swim across the English Channel, and the first to do so since 1875 when Captain Matthew Webb breast-stroked his way across the difficult waterway.

After a “good English breakfast” of ham and eggs, Burgess entered the water near the South Foreland light house in Dover, England, at 11:15 AM, and accompanied by a support boat, he began his swim in earnest heading southeast toward the French coast. Burgess would not touch land again for another 22 hours and 35 minutes, which to most rational people would be a ridiculous amount of time to spend in cold salty water.

The English Channel, known to the French as “La Manche”, is a large and highly variable waterway that separates the British Isles from Europe. On a clear day when looking over the Channel from Cap Gris Nez in France, one can easily see the White Cliffs of Dover, England, about 21 miles off in the distance to the north/northwest. Cargo ships, ferries, and all sorts of pleasure craft can be seen making their way through and about the area—one of the most highly trafficked waterways in the word. During the summer swimming season, the Channel can often look inviting and calm, but wait about an hour or so and that calm will suddenly give way to white cap waves and high winds that turn the placid channel into a treacherous maelstrom.

The water itself isn’t exactly pleasant either. Water temperatures even during swim season can range from 58° to 65°F (14° to 18°C), which makes hypothermia a real possibility for those not acclimated to it. There are also currents that, due to tidal activity, can cause major problems for Channel swimmers and mariners alike. These strong currents run northeast and southwest depending on the time of day and season with water flowing back and forth between the Atlantic Ocean and the frigid North Sea. Swimmers are generally compelled to take a somewhat meandering S-shaped path across the Channel because of these currents, turning the 21-mile as-the-crow-flies trip into a grueling trek of anywhere from 30-60 miles. Keep in mind, for those 30-60 miles there are other hazards including large cruising cargo ships and stinging jellyfish—the former of which a swimmer would rely on a support boat to deter, and the latter of which the swimmer simply has to suck up and bear.

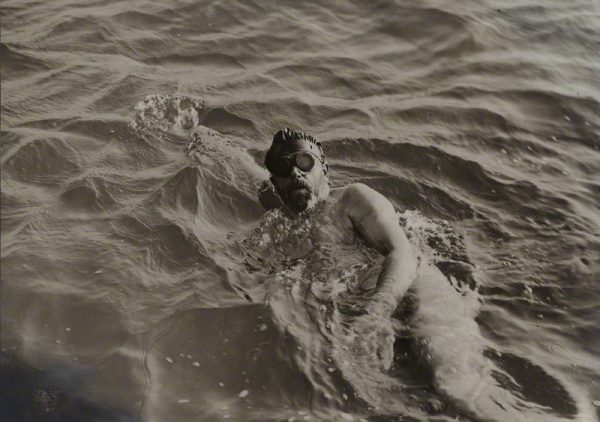

Burgess shown here in the water in 1911, doing his side stroke. He was the first successful Channel swimmer to wear goggles to protect his eyes from waves. Unlike contemporary models, his goggles were not waterproof. They were the type used by motorists.

The idea of swimming across this difficult body of water came in 1862 after a guy named William Hoskins rode on a bundle of straw from France to England. After that bizarre feat, the idea of swimming across the Channel unaided gained popularity as several eccentric, if not insane, swimming enthusiasts tried to make it across. Captain William Webb, the bravest of them (or nuttiest, depending on whom you asked), on August 25, 1875, became the first to accomplish the feat. A strong swimmer and an audacious adventurer, Webb managed to make the journey across in a little over 21 hours.

Burgess, like other smart Channel swimmers, chose a time of year when the weather would be mild enough for a swim. He also timed his departure with the tides hoping to use what he could to his advantage. Although his crossing ended up being successful, his start was anything but auspicious.

“It was during the first half of the swim that I had the worst time,” Burgess said, recounting his swim. “From the third to the fifth hours it was quite rough, and I got very much knocked about…During the first 12 hours, I had determined several times to give up and go back and start again when conditions were better.”

We need to keep in mind that these were the days before people had satellites and computer models to help predict the weather. Back then, weather prediction was little more than reading cryptic telegraph messages on conditions elsewhere, or looking at the horizon for storm clouds and sticking a thumb up in the air to feel the wind direction. Thus was the state of early 20th century meteorology.

Burgess swam on fighting the waves, winds, currents, jellyfish stings, and exhaustion. At one point, he claimed he had hallucinations, which were likely caused by the extreme conditions and fatigue. To help him along, the men in his support boat sang to him and cheered him on as the Channel currents pulled and pushed him back and forth on his journey. At regular intervals, they would pass him food and drinks on the end of a pole.

“I ate patent food1, chicken, and chocolate, and some tea, which, however, was not for food, but to cure indigestion,” recounted Burgess. According so some of his support crew, he also consumed hot milk and grapes.

Looking north by northeast, this is a view of the White Cliffs of Dover, England, from Cap Griz Nez, France. On a clear day you can easily see them across the Channel. The seas in this photo are visibly choppy. (Photo by V. Spadafora)

It is essential for Channel swimmers to keep up their strength by having food and drink passed to them during their swim. A lot of energy is required to not only maintain stroke but for the swimmers’ bodies to maintain heat. Hot drinks are also helpful for maintaining core temperature. Today, swimmers generally consume mostly energy bars, sports gels, and warm liquids.

Through the night, Burgess pressed on toward Calais, guided by his friends in the support boat. A fog over the water made keeping sight of the lighthouses on the French coast difficult to see. Many times the team had to correct course when the lights became visible. When dawn arrived, the team were relieved to see that they were only about three miles out from the nearest land. This was encouraging for Burgess, but he knew full well that the journey was far from over and that actually making landfall would be difficult.

One of the most frustrating things about a Channel crossing is that the tides close to shore can be cruel and can kill an otherwise fine-looking Channel swim in its final stretch. Many attempts, including at least one of Burgess’, ended within a mile of the French shore where currents would push exhausted swimmers north and south of the coast preventing them from making landfall. His successful attempt was no different as he ran into some serious issues near the French coast.

Burgess recounted, “The last 5 miles, the ‘swimmer’s mile’, as they call it, took me seven and a half hours to do, but I never thought of coming out…I was shot past Grisnez Point [sic] by the tide at a distance of 400 yards from the shore. I made a race to get in west of the point where there is a sandy spit, but was caught by the off-setting current and carried around the point again only 100 yards or so away.”

This is a view of Cap Griz Nez in France looking north. About 21 miles in the distance is England. This is where Burgess ended up after his triumphant swim. (Photo by V. Spadafora)

Burgess wasn’t alone in the water for his final push. His friend and fellow Channel enthusiast J. Weidman jumped in around 6:30 AM and swam alongside Burgess. As they finally neared the shallow waters of the French shore, Weidman told Burgess to put his feet down, and that the water was shallow enough to walk. Burgess did so and waded uneasily to shore. When he finally reached dry land, he staggered up to the dunes, collapsed, and in his words, “had a jolly good cry.” In all, according to the support boat captain’s estimate, Burgess had covered 60 miles because of currents—almost 3 times longer than the actual distance between Great Britain and France.

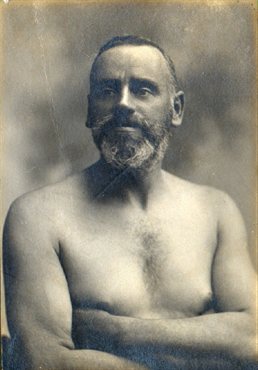

Born in Rotherham in South Yorkshire, Great Britain, on June 15, 1872, Thomas William “Bill” Burgess was the son of a blacksmith. He learned to swim at an early age and kept at it even when his family moved to London. There Burgess joined a swimming club and spent many of his days swimming up and down the Thames River.

Burgess’ dad worked for the Earl of Shrewsbury who seemed to take a general liking to the Burgess family. Sometime in 1889, the Earl offered Burgess a job in Paris running the Earl’s French branch of his tire business. Burgess knew an opportunity when he saw one, and accepted the job. Over the next few years, Burgess got married, had a couple of kids, started a business of his own, and led a generally good life. So much did Burgess enjoy France that he lived there for the rest of his life.

Swimming though was always Burgess’ passion, and he kept at it. In 1900, Burgess competed in the Paris Olympics. Representing Great Britain, Burgess competed in the 1,000m freestyle, 4000m freestyle (where he finished 4th), and the 200m backstroke. What was funny back then was that athletes could compete for more than one country if one of the events was a team event. In Burgess’ case, he won a bronze medal with the French water polo team.

It wasn’t until 1904 that Burgess began his Channel-swimming adventure with his first attempt on August 19. Over the next 7 years, Burgess’ progress was followed by the press and public, as many believed he had the best chance of being the one to succeed in repeating Webb’s feat. On one of his attempts in 1908, Burgess set records for distance and time in the water after having swam over 60 miles in a little under 22 hours 45 minutes. Frustratingly enough for Burgess, he had to end his swim close to the French shore because the currents and winds coming from off the mainland prevented him from making landfall.

The two swimmers seem to have had very different personalities. Burgess was an enthusiast whose day job in Paris was stable. Webb, formerly a mariner, was a known risk taker, having once jumped into the freezing Atlantic Ocean to save a shipmate during a storm (sadly, Webb wasn’t able to save the man). Burgess, although just as crazy if not persistent in trying to make the crossing so many times, seemed more of a tactician and less of a straight up risk-taker. That’s not to say that Webb simply jumped in the water with no prior planning and hoped everything would turn out okay—he had a support group made up of three boats to help him along.

A map showing Webb’s and Burgess’ respective Channel-crossing routes. As you can see, the tides and currents prevent swimmers from swimming straight across. Burgess’ route seemed particularly affected as he seemed to get swept south, backwards, then south again before eventually getting across.

When Webb first made the channel crossing, he primarily used the breast stroke, which was the preferred stroke by expert swimmers at that time. The front crawl, a fast stroke used by contemporary swimmers, was not in regular use then even though one could argue that it’s the best way to move over the water. Indeed, the breast stroke is a perfectly fine stroke, but it’s a slower stroke. Burgess for his part used the overarm sidestroke (with some backstroke thrown in there), which was popular, if not somewhat unsightly. “An expert swimmer friend told me the overarm side stroke was the ugliest stroke,” said Burgess, “and that I was the ugliest swimmer he knew.”

In their post-Channel-swim lives, Burgess went back to his day job running his tire business refusing for the most part to do any exhibitions or feats to further capitalize on his fame. Webb on the other hand, wasn’t so fortunate.

After Webb’s Channel crossing, the money he gained trading on his fame doing advertisements, lectures, and exhibitions began to wane as time went on. To make money, Webb would perform various daring feats for audiences. However, it was his last feat in 1883 when he tried to swim the whirlpool rapids on the Niagara River below Niagara Falls that killed him. Webb was paid $10,000 to swim through the rapids downriver from the falls, and through the infamous whirlpool. Webb made it into the whirlpool but never came out. His body was found 4 days later downriver. Surprisingly, Webb’s death was not ruled to be from drowning nor from being smashed on the rocks—but from the pressure of the water in the whirlpool.

Burgess considered performing some feats, but in the end, he chose to use his swimming enthusiasm to coach future Channel swimmers. He even went so far as to buy a house at Cap Griz Nez2 from where he could base his coaching during the swim season.

Gertrude Ederle, an Olympic gold medalist and world-class distance swimmer had English Channel ambitions of her own. Having already proven to be one of the finest athletes in the world, Ederle set her sights on becoming the first woman to make the Channel crossing. After her first channel attempt ended in failure (due to her then coach touching her while she was in the water thereby disqualifying her), Ederle hired Burgess to be her personal coach. It proved to be a pretty smart move on her part.

Burgess is shown here rubbing goose fat over Gertrude Ederle’s body both to make her slip through the water easier and to insulate her. Ederle, the first woman to cross the English Channel, had hired Burgess as her coach. (Courtesy of the Dover Museum)

Ederle was a really fast swimmer. She used the contemporary crawl (the stroke that competitive distance swimmers use today) as her primary stroke, which allowed her to glide over the water quickly. Taking her speed, strength, and high endurance into account, Burgess helped Ederle plot a Z-shaped route across the channel, hoping that her speed would allow her to avoid some of the worst tides.

Ederle set out from France on August 6, 1926 (she made the crossing from France to England). As is always the case with the English Channel, her crossing didn’t exactly go smoothly. She got caught in some mid-Channel squalls that caused Burgess who was in one of the support boats to fear for her life. He twice tried to get Ederle to leave the water, not because he was worried that Ederle was exhausted but because the sea was getting rough. On one of those occasions when Burgess called out to Ederle and told her it was time to come onto the boat, it was reported that she lifted her head from the water and replied, “What for?” before continuing on her historic way. Ederle finally made landfall in England 14 hours and 34 minutes later.

(There is no way to do Gertrude Ederle justice in just a few paragraphs here. For a bit more on her life and her amazing Channel crossing, please take a look at this, this, and this.)

Burgess is remembered most for being Ederle’s coach during her historic Channel swim, but his own Channel swim contributions toward long-distance swimming cannot be understated. He continued coaching, swimming, and being an advocate for swimming for the rest of his life. He was a well-respected figure in the long-distance swimming world whose advice was often sought by later aspiring English Channel swimmers. Except for one period during during WWII after the Germans invaded France3, Burgess lived a relatively quiet life.

Thomas William “Bill” Burgess died in Paris on July 2, 1950.