We know full well that stew is always better on the second day!

09/26/2017

Updated on 04/10/2023

Editor’s Note: SilverMedals.net defines the second day of school for the Little Rock Nine as the second day they were able to actually enter the school. Their first day was supposed to be 9/4/57, but they were turned away by soldiers from the Arkansas National Guard. The first day they were actually able to enter Little Rock Central High School, 9/23/57, was a shortened day due to the presence violent mob on the school grounds. The second day the Little Rock Nine were able to enter, 9/25/57, was a full day and is the day SM focuses on here. Just to cover all our bases, this article also covers the second “full” day of school, which came on 9/26/57.

The decision handed down in 1954 by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka case put an end to the idea of “separate but equal” in the U.S. and effectively ruled that segregation on the basis of race was unconstitutional. It was no longer permissible for public institutions to have separate bathrooms for black people and white people, separate offices for black people and white people, or more to the point of this article, separate schools for black people and white people. For 58 years following the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, this type of enforced segregation was the law of the land. It didn’t stop there: in many parts of America, it was against the law during to NOT segregate certain facilities. So when the 1954 decision came down, it sent waves of resentment through many southern U.S. communities where segregation was the norm. This was particularly acute when it came to desegregating schools. There was a significant population of white people in the south who were adamantly against having white and black children co-exist in an educational setting and were very vocal in their disapproval.

Classes at Little Rock Central High School for the 1957-58 school year began on September 4 for most students. It was to be a very different year from previous ones because it would be the first year that black and white children would attend classes together at the high school level. As part of the city’s gradual school integration plan and in order to comply with the Brown decision, nine black African-American students were chosen to be the first to integrate with the white students at Little Rock Central High. The students were specifically chosen because of their scholastic aptitude and maturity, and the belief among many area black activists and school officials that they would conduct themselves well during what was sure to be a difficult time. They were coached by a local NAACP activist named Daisy Bates on how to handle the media and likely protests, and it was at her house where many media conferences took place. Collectively known as the “Little Rock Nine”, they were Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Carlotta Walls, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo.

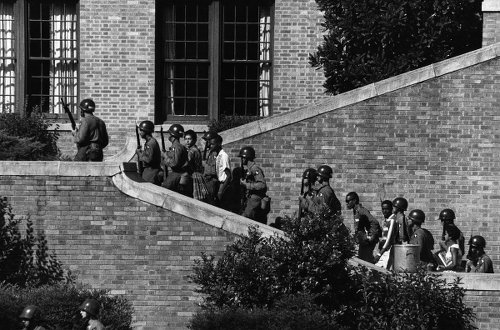

Soldiers of the Arkansas National Guard, as ordered by Governor Faubus, refused to allow the black students to enter Little Rock Central High School. (U.S. National Archives)

On the morning of September 4, eight of the Little Rock Nine students arrived together, with the ninth, Elizabeth Eckford traveling separately because of a miscommunication. When the eight tried to enter the high school, they were harassed by an angry mob of white anti-integration protesters. Showing a degree of fortitude and patience that few children of any race have at their age, the eight black students proceeded quietly toward the school with the help of their parents and ministers who were there to ensure their safety and to give moral support to the kids. When they approached the school having walked through a cackling gauntlet of white hate, the black students were stopped by a line of uniformed Arkansas National Guardsmen who, under orders from Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus, were there to prevent the black children from entering the school. Governor Faubus had taken a strong position against desegregation and in flagrant violation of Federal law used his troops to prevent the high school’s integration. With no recourse, the black students turned back and headed home together. As for Eckford, the ninth black student who traveled alone, things went a little bit differently.

Eckford, who was 16 at the time, had not been notified that the nine black children were to meet at Bates’ house before proceeding together to the high school. Her family did not have a telephone and it had been erroneously assumed that she and her family knew of the plan to travel together. So while the other 8 children endured the hate and racial epithets spewed at them while altogether, the unfortunate Eckford had to suffer alone.

Probably one of the most pointed images from the Black Civil Rights Movement, above to the right of center we see 16-year-old Elizabeth Eckford as she walked on toward Little Rock Central High School surrounded by a crowd of angry white protesters. Just behind Eckford in the left center of the photograph, we see a 15-year-old white student named Hazel Bryan yelling racial slurs and other insults at Eckford. Bryan’s vicious and hateful expression put a face on the protesters that disturbed many Americans. Bryan later apologized to Eckford in 1963. Photo by Will Counts of the Arkansas-Democrat.

Surrounded by seething white protestors, Eckford tried to walk to school, but because of the menacing crowd, she prudently decided to turn back and head home. The entire time, she was harassed, spat on, threatened, and called just about every racist epithet imaginable. She stopped at a bus stop and sat on a bench hoping to get a bus home and out of the situation. While there, only a few feet away from her, hateful white protestors continued to jeer at her. The entire time, Eckford kept quiet, with her head down, not interacting with anyone. Several times, reporters tried to get her to speak, but Eckford remained firm, if not terrified. Finally, a well-meaning white woman named Grace Lorch took pity on Eckford and sat with her until the bus arrived.

The result from that failed first day was that the Little Rock Nine were unable to have their first day of school, and Governor Faubus was acting in violation of federal law.

Governor Orval Faubus for what it’s worth, had previously been considered a moderate when it came to race relations, and had actually received support from the black population in the state during his last election because of what were considered his “progressive” values. It’s important to put this into context. Back then in Arkansas, it didn’t take much to be a political moderate or racial “progressive”. All it took was some honeyed words, an acknowledgement that the Earth was round, and a few statements praising Roosevelt’s New Deal. Governor Faubus was just such a man. He was also a craven, opportunistic, liar whose main goal was to keep his governorship intact even if it meant that nine innocent black children had to be put through hell.

Having narrowly won his previous election, Faubus was facing a difficult and close future election. So to win over the idiotic wing of what was a far different Democratic Party than today’s, Faubus decided to take a hard line against desegregation in the hopes that he’d carry the next election. Running with that tactic, Faubus came out strongly against desegregation and, under the guise of “preventing violence”, he sent in the Arkansas National Guard to “remove the cause” of that violence, which in his warped view was the nine black students who wanted to go to school. He even put forth a dubious claim, as mentioned here in a September 15, 1957, interview with journalist Mike Wallace, that armed bands of both white and black activists were descending on Little Rock ready to cause violence. In his defense, it was true that many out of staters did indeed show up to cause trouble, but they weren’t radical black leaders. Instead they were freakishly stupid white people who were staunchly pro-segregation. So instead of using his National Guard to protect the students, Faubus used them to keep the kids out, making it clear that he was not going to comply with the Federal Court’s ruling then or anytime later.

The entire spectacle was staged by Faubus to show his constituents that he meant business when it came to desegregation. What made his actions even more despicable is that at some level he had to have known that his scheme wouldn’t have worked, and that the federal government would have had to step in. That being the case, Faubus tried to score political points while leaving the Little Rock Nine to deal with angry white mobs and protesters.

Images from the day’s events were broadcast across the U.S. on TV and in newsreels. Newspapers also carried pictures and accounts of the confrontation in Little Rock. Many Americans of all races, including a majority people in the south, were disgusted and outraged by the treatment of the Little Rock Nine. Even some adamant segregationists thought the treatment of the black students was deplorable.

The “Little Rock Nine”. Back row, left to right: Terrence Roberts, Melba Pattillo, Ernest Green, Carlotta Walls, Daisy Bates (NAACP activist, not a student), Jefferson Thomas. Front row, left to right: Thelma Motehrshed, Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Gloria Ray.

In looking to force the Governor’s hand, the local Little Rock chapter of the NAACP sought an injunction in federal court against Governor Faubus and his deployment of the National Guard, demanding that the nine black students be allowed admission to Little Rock Central High. Governor Faubus continued to assert his position that the National Guard acted as it did in order to prevent a riot and that as governor he had the right to ignore federal statute and suspend certain rights for a short period of time if he thought his action would protect Little Rock citizens from violence. The governor was walking a fine line in that he admitted that desegregation was the law and that it would happen eventually, but that the presence of the nine black students created a dangerous situation. He felt that it stood to reason that he should “remove the source” of the problem, that “source” being the black kids.

Federal court Judge Ronald Davies didn’t buy it. He ruled that the governor was acting outside of the law and demanded he allow the children to enter school. Insisting that it was his right to keep the peace by keeping the black kids out, the governor refused to comply with Davies’ order. Meanwhile the Little Rock Nine were being tutored by volunteers while the events played out.

One person who was particularly displeased with the turn of events in Little Rock was U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The President was no civil rights activist by any stretch, but instead he was more of a moderate conservative, who tried to appeal to other moderates to see the situation come to a suitable end. Beyond that, President Eisenhower was a firm believer in the rule of law, and it was the Supreme Court, who in Brown v. the Board of Education ruled that the idea of “separate but equal” schools and other institutions was unfeasible and unconstitutional. Therefore, to President Eisenhower and anyone else with even a passing understanding of federal law, it was imperative that the Little Rock Nine be granted admittance into Little Rock Central High School. To achieve that end in the most prudent manner, President Eisenhower summoned Governor Faubus to his summer vacation place in Newport, RI, to get a deal done. After the two men spoke, the President came away thinking that the situation would be quieted and that Governor Faubus would see reason. Eisenhower was very wrong.

All nine of the black children seeking admittance into Little Rock Central High School met at Daisy Bates’ house on the morning of Monday, September 23, 1957, and journeyed to school together. It was hoped that the nine black students would be able to slip into school early before anyone saw them, but their plans were thwarted by the nasty mob that also turned up early. Governor Faubus had indeed kept up his end of the bargain and didn’t interfere with the students trying to enter, but his was a more pointed non-interference. In what was at best a display of willful obtuseness, or at worst a flagrant dismissal of the president’s wishes and a reprehensible lack of compassion for nine black children, Governor Faubus instead of using the National Guard to keep peace while the Little Rock Nine went to school, did exactly as he was ordered by the federal injunction and sent the Guard home leaving the situation up to the local police, who by their own admission and very much to the knowledge of everyone involved, were not equipped to deal with the situation. Technically the Governor was complying with the judge’s order and was simply letting the situation take its course, but a more compassionate leader would have used the guard to protect the black kids rather than turn them away. In short, Faubus threw the Little Rock Nine to the lions. What came next was a full-on riot.

Alex Wilson, the black man pictured here on the left with the racist white guy on his back trying to choke him, was a well-respected editor of the Tri-State Defender, a newspaper out of Memphis, TN. Pictured here on Sept. 23, 1957, Wilson was in Little Rock to cover the Little Rock Nine as they made their second attempt at a first day of school. While trying to cover the event, the white crowd turned on him and assaulted him repeatedly. By the time Wilson was able to get to his car and escape, he was a bloody mess. A staunch newspaper man to the core, Wilson never saw a doctor but instead went right back to his hotel room and got to work on his article recounting the day’s events. He had a deadline to meet and wasn’t about to let a near riot and a brick to the head stop him. Courtesy of the Will Counts Collection: Indiana University Archives.

The Little Rock police, which numbered about a couple dozen in all present, did what they could to prevent any serious bloodshed but they were too outnumbered. They managed to clear the way for the kids to actually get into the school by a side entrance, but the situation was perilous. Once the crowd learned that the Little Rock Nine had made it into in the school, they began rioting, with some of the more radical (or stupid) elements of the crowd calling for lynchings.

Black journalists, there to cover the events, were harassed and driven off by the white mob. One journalist, Alex Wilson a well-respected editor of the Memphis-based Tri-State Defender, got pushed, kicked, punched, choked, hit in the head with a brick, and beaten up. Arrests were made, fights broke out, objects were hurled. The police began to fear for the students’ lives and decided to evacuate the 9 black children before the crowd stormed the school. Just before noon, the kids were spirited out of the building by school officials and police and into vehicles waiting for them in the back, out of sight of most of the protesters. With orders to “drive and don’t stop for anything” the cars sped away from the school and the crowd. Things cooled off when the crowd learned of the black kids’ escape and the rest of the school day went on. Eventually the nine black students made their ways back to their homes.

Thus ended the first day of school for the Little Rock Nine — a fear-filled half-day with a riot.

The next day as images and news reports of the situation in Arkansas were broadcast across the U.S., many people were further disturbed by the turn of events and began calling for action, while other more racist groups felt empowered by the apparent “victory” of the protesters over the black students and “oppressive” federal government. President Eisenhower personally felt annoyed with the Arkansas Governor in whom he thought he had found a moderate partner in bringing the situation to a peaceful close. After receiving a personal plea from Little Rock mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann who was trying to manage the situation as best he could, President Eisenhower was compelled to assert federal authority in a way that would remind many in the south of the Reconstruction. The President issued an executive order that federalized 10,000 soldiers of the Arkansas National Guard, thus putting them under the direct control of the Secretary of Defense outside the bounds of Governor Faubus’ authority, and he called for the deployment of U.S. Army personnel to Little Rock. That night, President Eisenhower addressed the nation, and announced his plan to send federal troops into Little Rock to take control of the situation. Although such a move was within the realm of possibility to all involved, even expected to some, the President’s action was still somewhat of a shock.

The Little Rock Nine as they entered Little Rock Central High School, surrounded by federal troops of the 1st Airborne Battle Group of the 327th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. Sept. 25, 1957. Photo credit: AP

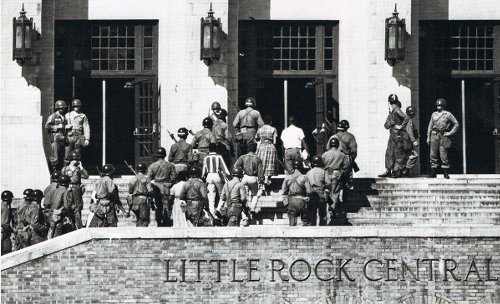

On the night between September 24 – 25, 1957, several dozen military trucks and jeeps rolled into Little Rock carrying 1,600 soldiers from the 327th Infantry Regiment, of the 101st Airborne Division. The group had driven through the night from their base in Kentucky under orders to cordon off a secure area around Little Rock Central High School and to protect the children from whatever riots or protests came. The “Screaming Eagles,” as the 101st was known, was a trusted group of elite paratroopers who more than a decade earlier played vital roles in several major operations during WWII, including among others the Allied landings at Normandy, Operation Market Garden, and Bastogne. When they arrived, the troops immediately went to work setting up checkpoints and securing areas around the school.

When Little Rock residents awoke that morning, those near the school saw a full-on military occupation. It was almost surreal. Soldiers in combat fatigues carrying M-1 rifles with fixed bayonets were stationed in various strategic locations on and around the school and in other locations in the nearby neighborhoods. They formed up into platoons and squads ready to take on any protesters who showed up and ready to react to any changes in the situation. Jeeps with machine guns could be seen at several strategic locations while overhead military helicopters flew surveillance over the scene. There was even a backup force of U.S. soldiers standing by at the airport in case things got rough.

At Mrs. Bates’ house, the students and their families were briefed on the protocol for going to school. They would all meet at the Bates’ house and together they would go to school in cars escorted by two military jeeps, one in front and one in back, both carrying soldiers with rifles and machine guns. Once inside the school, each of the Little Rock Nine were assigned a personal body guard who would wait outside their classrooms until their class was over, and then escort them to the next class. At the end of the day, they would be escorted to cars waiting out front and driven home with soldiers in jeeps again ensuring their safe arrival. These bodyguards were also to follow the children to gym, to lunch, to after school sports activities.

Two of the Little Rock Nine emerge from a car owned by the U.S. military. If you look closely at the left shoulder patch of the soldiers whose backs are turned to the camera, you can just make out the “screaming eagle” patch worn by all soldiers of the 101st. Photo credit: United States National Archives.

When the motorcade with the children arrived at school, they were met with the same fierce mob that had been there the previous days, except they were somewhat cowed by the presence of the soldiers. The mob chanted and hurled insults. An effigy of a black student was hung from a nearby tree. The crowd tried to march and block the entrance to the school, but the soldiers forced the crowds back, and made several arrests. Soldiers cordoned off areas, held back crowds, and even forced people at bayonet point to back off from the school grounds. In several instances some of the more violent protesters were clubbed by soldiers and arrested.

Despite the protesters’ best efforts, they were completely overwhelmed by the 101st. By the time the students arrived, a clear path had been made for their entrance. With careful coordination and an armed phalanx of paratroopers around them, the Little Rock Nine walked right in through the front door of Little Rock Central High School.

Inside the school, teachers and students tried to get on with the day the best they could. Before classes started earlier in the day, U.S. Army Major General Edwin A. Walker addressed the students during an assembly warning them against staging any demonstrations. Attendance that day was down, partly out of protest, but also out of parents’ worries of riots and violence.

After the dramatic events of the 25th, nobody knew what to expect on the 26th. Throughout the previous night, soldiers kept watch over the school area. Governor Faubus for his part, was livid. During a speech he gave on the evening of the 26th, he passionately railed against the “military occupation” of Little Rock and accused the soldiers of bayoneting and bludgeoning citizens. He spoke of federal agents “swarming” the city and how the city was being governed by “police state methods”. It is true that there were some injuries among the protesters, but they were nowhere near to the level that Faubus was insisting. In fact, events on the 26th, the second full day of school (third day overall) for the Little Rock Nine went off rather peacefully.

On the morning of the 26th, just as they had the day before, the soldiers met the kids at Bates’ house and together proceeded to the school under armed guard. When they arrived at school, contrary to Faubus’ warnings of further bloodshed and riot, there was no mob whatsoever. Not a single segregationist protester was present. The only real “crowd” present was the gaggle of newspaper and TV reporters covering what they thought would be another incident. Except for the verbal abuse the Little Rock Nine endured while in school, that day and those after were relatively peaceful. The situation had been more or less “normalized”.

The federal troops stuck around until November, at which time they pulled out of Little Rock and turned protection of the children over to the federalized Arkansas National Guard. These Guard troops were made up of troops from other parts of Arkansas who had fewer ties to the Little Rock area. Each student continued to have a personal body guard and there would still be a military presence in front of the Little Rock Central High School for the rest of the year. For the most part, the National Guard did a good job of keeping order but they couldn’t be everywhere.

As great as it was for the black students to have such overt protection around them, the harassment didn’t stop. In the bathrooms and in locker rooms, some of the more rowdy white students picked on the black students, even going to far as to physically assault them. One student described being pushed onto broken glass. Melba Pattillo had acid sprayed in her face (luckily it wasn’t very strong). The Little Rock Nine had been instructed by those adults advising them to not fight back but instead to try to walk away from such incidents. For the most part the black students did that except for one.

Federal troops standing guard at the front entrance of Little Rock Central High School, September 26, 1957.

Minnijean Brown had been having as tough a time as the other students. In one instance her bodyguard had to run into the bathroom to save her because a group of white girls were holding her head down in the toilet. Having been subjected to repeated verbal abuse from some white boys in the cafeteria, Minnijean Brown dropped her lunch tray on them, which included a large bowl of chili. That earned her a suspension. The white girl of course, got off with just some chili stains on her clothes. During the incident, the cafeteria workers, the vast majority of whom were black, broke into applause when Brown dumped the chili on the white girl. Several weeks later during another incident, Brown, after having been assaulted by another white girl, was expelled after having turned and referred to her as “white trash”. She finished her schooling elsewhere.

The one who seemed to have the best year was Ernest Green who at the end of the school year became the first black student to graduate from Little Rock Central High School as part of the class of ‘58. As for the remaining seven, things only got harder.

Governor Faubus and his racist constituency may have lost the battle, but they were determined to win the war, or so they thought. Still taking a staunchly segregationist position, Faubus, in an extreme example of cutting off his nose to spite his face, used his power to halt desegregation and closed all Little Rock public high schools, black and white, for the ‘58-’59 school year. That’s right, so vehemently were they against having black and whites sit in classes together, he and his cohort of morons decided to deny a free high-school education to all Little Rock students. The ploy worked about as well as you’d expect. Parents and students were angry after having lost a year of school, and the racial divides deepened.

As for the rest of the Little Rock Nine, all eventually graduated.

President Eisenhower is a difficult figure to label when it comes to Civil Rights. For the most part, he was instrumental in completing the desegregation of the army, which was begun by his predecessor. He also took strong action in the case of the Little Rock Nine. Indeed he was also against racial discrimination. However, the President did not agree with Brown v. the Board of Education at least at first (in 1967 years after he left office, President Eisenhower said, “there can be no question the judgement of the court was right.” But while he was in office, Eisenhower voiced several times his belief that culture cannot be changed by laws.

As things were, President Eisenhower was a right-leaning moderate who despite his own distaste for racism and prejudice, could not help but relate to whites more. For segregationists, Eisenhower was a bane, a figure of oppressive federal authority. To desegregationists, he was slow to act and an impediment to quicker and broader integration. It seems the latter is a more true statement considering other events going on at the time where his inaction or slow response gave mixed signals to those who were pro-segregation and more often than not emboldened them in the violence and harassment they inflicted on black students and activists. For these reasons, rightly or wrongly, President Eisenhower is not viewed as a major figure or proponent of black Civil Rights.

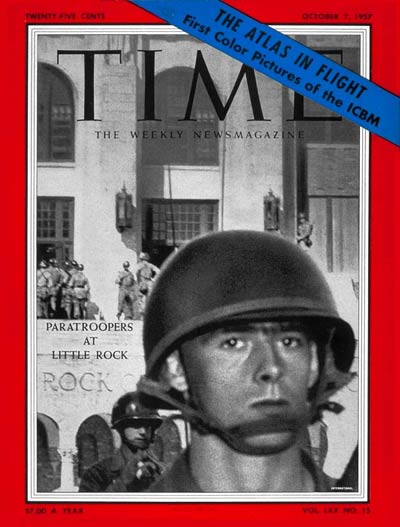

Cover of the October 7, 1957, issue of Time Magazine.

It was on that second day of school, the 25th, when the Little Rock Nine managed to enter the school when the reality of Brown really sunk in. Whether or not President Eisenhower agreed with desegregation, he showed that the federal government would enforce federal laws pertaining to race and desegregation. Unfortunately, it was an uneven enforcement. Violence and harassment occurred in several other states, most notably Tennessee and South Carolina where students did not have the luxury of federal involvement, but instead had to weather the assaults, threats, and harassment on their own. In the end, many black students in those places returned to the safety of their local black schools or went to schools outside their districts in order to avoid further violence.

It was also on that second day that the courageous Little Rock Nine finally got the backing and protection of the federal government. As much as it is a shame that it took 1,600 highly trained U.S. Army paratroopers to get those kids the education they deserved, the episode served as some reassurance to some civil rights proponents that progress was being made.

The 26th, the second full day for the Little Rock Nine, was also notable because of the lack of protest or violence. It was the day where the victory for desegregationists was fully realized, all for the simple reason that the mob gave up. Governor Faubus would continue to warn his constituents about the likely violence and mayhem caused by forced integration, but as time went on, his warnings became more and more baseless.

As for the Little Rock Nine, their courage and poise were a model for other students and activists across the U.S. who were suffering through similar situations, and continue to be an inspiration to black Americans for whom racism is still a firm reality that they must deal with every day. The nine black students also left an indelible impression on the soldiers who were there to protect them. One such soldier was James Dameron who, according to this article, was a young white Lieutenant with the federal force that escorted the Little Rock Nine into the school. He said, “I can honestly say that I had the utmost respect and admiration for the students then and now. It took a lot of courage to do what they did and fortitude to endure what they had to confront in Central High School. I cannot begin to imagine what psychological and physical abuse they had to put up with, even with the troops there.”